Shocking Proof of Black Hole Pairs Found: Is the Universe Hiding More Secrets?

Imagine a cosmic dance between two colossal black holes, swirling around each other in the depths of space. For years, these enigmatic phenomena were thought to be mere figments of science fiction, but now, astronomers have unveiled a shocking reality: we have an actual image of two black holes engaged in a celestial waltz. This groundbreaking discovery confirms a long-held suspicion in the scientific community: black hole pairs are indeed real.

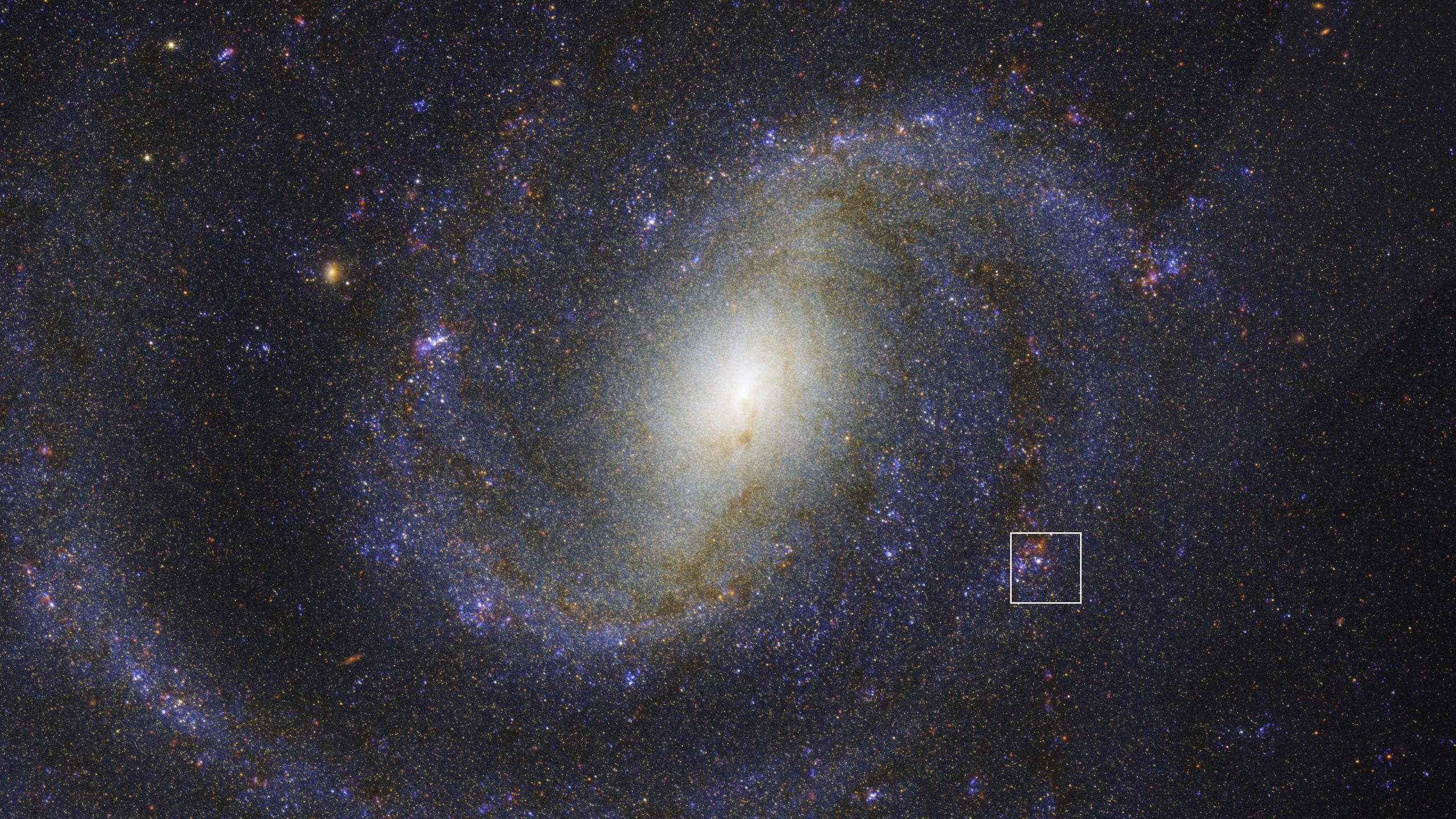

Captured by a sophisticated radio telescope, this incredible image showcases two black holes in the distant quasar known as OJ 287. Quasars, the universe's most brilliant objects, sit at the centers of far-off galaxies, illuminated by supermassive black holes that are gorging on gas and dust. As this material spirals inward, it heats up to extreme temperatures, emitting vast amounts of energy that we can detect from billions of light-years away.

OJ 287 is particularly fascinating not just for its luminosity—it's bright enough for amateur astronomers to observe—but also for its unpredictable behavior. Scientists noticed that its brightness fluctuates on a regular cycle, leading them to hypothesize the presence of two black holes orbiting each other within its core. Now, thanks to advanced imaging techniques, they have transformed that hypothesis into reality.

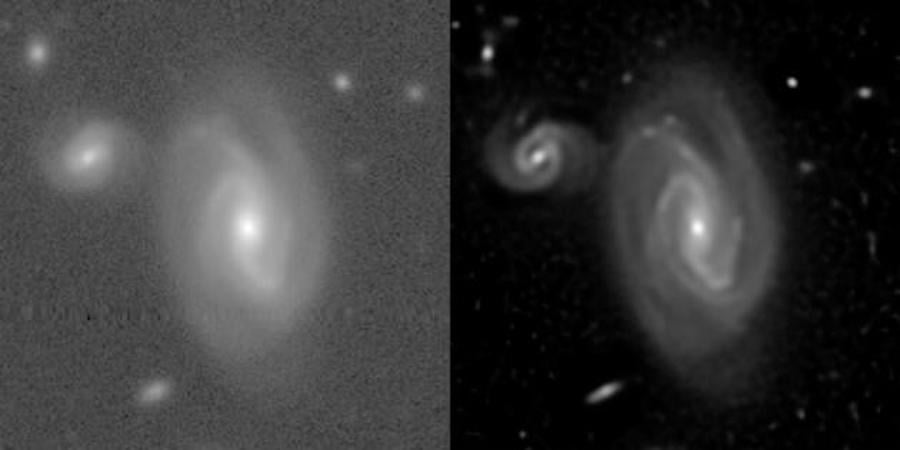

An international team of astronomers succeeded in photographing these two black holes side by side, right where they theorized they would be, putting to rest a question that has lingered for four decades: do black hole pairs exist? “For the first time, we managed to get an image of two black holes circling each other,” said Mauri Valtonen from the University of Turku. “They might be perfectly black, but the intense jets of particles they emit give us a way to spot them.”

Getting this image wasn’t a walk in the park. Regular telescopes struggle to differentiate between two black holes since they appear as a single point of light. However, radio telescopes, capable of achieving up to 100,000 times greater resolution, finally provided the clarity needed to capture this extraordinary moment.

OJ 287 has been a part of our cosmic view for over a century, captured in old photographs long before we understood what it was. The concept of black holes didn’t even exist back then; astronomers were merely photographing nearby stars. The turning point came in 1982 when a master’s student named Aimo Sillanpää noticed a periodic brightness change every 12 years. Curiosity sparked, leading to hundreds of astronomers investigating this phenomenon.

Eventually, Lankeswar Dey, a doctoral researcher from Mumbai, solved the orbital mystery four years ago but needed the visual confirmation that only the latest radio telescopes could provide. NASA’s TESS satellite had detected light from both black holes, but it lacked the detail needed to distinguish them individually.

In an exciting twist, researchers even observed a peculiar feature: one of the black holes, the smaller of the two, emits a jet of particles that twists and bends like a garden hose under pressure. This “wagging tail” phenomenon is a result of the smaller black hole dynamically orbiting the larger one, causing the jet to change direction as it speeds up and slows down in its orbit.

Valtonen explained how they achieved this stunning image, stating, “The image was captured using a radio telescope system that included the RadioAstron satellite, which operated a decade ago.” This satellite’s radio antenna, reaching halfway to the Moon, significantly amplified the image's resolution compared to Earth-based telescopes.

This remarkable photo is more than just a captivating image; it’s tangible proof that black holes don’t operate in isolation. Some of them, like those in OJ 287, have been moving together for millions of years. Now, for the first time, we’ve glimpsed this cosmic reality with our own eyes. The full study was published in the esteemed journal The Astrophysical Journal.