Unbelievable Discovery on the Moon: Hidden Water-Bearing Meteorite Revealed!

Have you ever thought about what secrets the Moon might be hiding? A shocking new discovery from the far side of the Moon has unveiled that it holds microscopic treasures unlike anything we've seen before.

A detailed study of lunar material gathered during China's Chang'e-6 mission has unearthed tiny specks of dust from a rare type of water-bearing meteorite, known as the CI chondrite. These meteoric treasures are so fragile that they usually crumble upon entering Earth’s atmosphere, making this finding nothing short of extraordinary.

This marks the first time scientists have confirmed the presence of CI chondrites on the Moon—small fragments from asteroids that are usually rich in water and volatile compounds. Imagine that! These meteorites can contain up to 20% of their weight in water, but most don’t survive long enough to reach Earth due to their soft, crumbly structure.

Even though the Moon lacks an atmosphere to burn up incoming rocks, the high speeds at which objects collide with its surface typically result in vaporization or melting. Hence, the chances of finding such delicate materials on the Moon seemed almost impossible.

Led by geochemists Jintuan Wang and Zhiming Chen from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, researchers meticulously sifted through over 5,000 fragments of lunar material. They targeted samples from the Apollo Basin, nestled within the colossal South Pole-Aitken Basin—an ideal site for ancient impact debris.

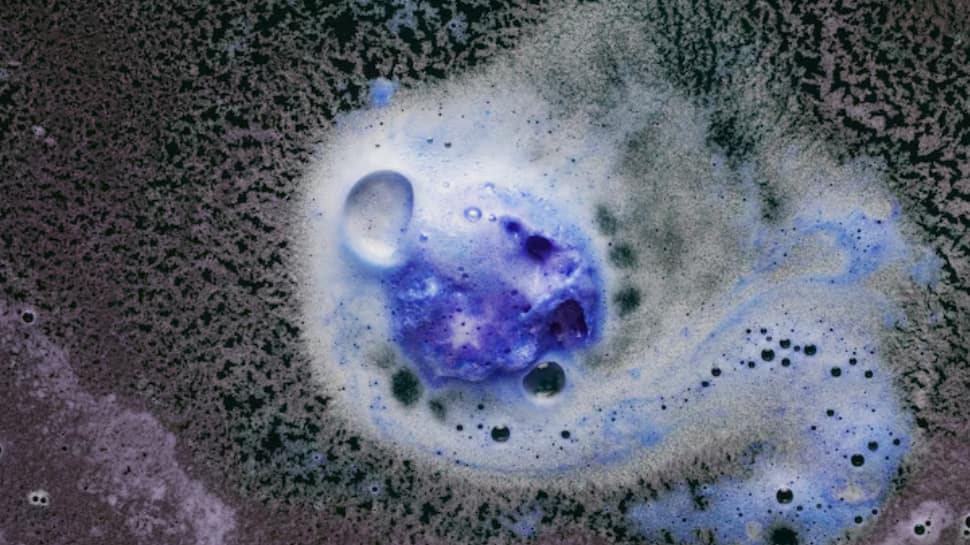

Focusing on olivine, a mineral frequently found in both volcanic rocks and meteorites, the team identified several olivine-bearing fragments. After extensive analysis using advanced techniques like scanning electron microscopy and secondary ion mass spectrometry, they pinpointed seven clasts that matched the chemical signatures of CI chondrites.

The study revealed that these clasts exhibited porphyritic structures, indicating they had rapidly cooled post-impact. But here’s the kicker: the iron-to-manganese ratios and other chemical signatures found in these fragments contradicted what would be expected from lunar or earthly origins, suggesting they originated from a CI chondrite asteroid that collided with the Moon and preserved its ancient chemistry.

This groundbreaking finding provides the first concrete evidence that CI chondrites have impacted the Moon since its formation, and it appears that the Moon could actually be a better environment for preserving such meteorite remnants than Earth itself. The researchers estimate that CI chondrites could account for as much as 30% of the Moon’s meteorite collection!

For years, scientists have speculated that these elusive CI chondrites may have played a crucial role in delivering water and volatile compounds to both the Earth and Moon. Now, these seven tiny grains of dust lend credence to that theory.

As we look toward future lunar sample missions, the implications of this discovery could reshape our understanding of the Moon’s history and its connection to Earth. The team concludes, “Our integrated methodology for identifying exogenous materials offers a valuable tool for reassessing chondrite proportions in the inner Solar System.” This is indeed a monumental step forward in lunar research.