Underwater Discovery of Ancient Hominin Fossils Challenges Understanding of Early Human Life in Southeast Asia

Deep beneath the waves of the Indian Ocean, just off the coast of Indonesia, a remarkable discovery is reshaping our understanding of early human life in Southeast Asia. In a region between the islands of Java and Madura, scientists have unearthed what they are heralding as the first underwater hominin fossil site ever identified in this part of the world. This discovery not only includes a significant collection of fossils but also serves as the first tangible evidence of the prehistoric continent known as Sundaland, a landmass that once linked much of Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene epoch.

The focus of this groundbreaking find is on two skull fragments attributed to the species Homo erectus, an early ancestor of modern humans. These bones, which had been concealed under layers of silt and sand for over 140,000 years, were brought to light during marine sand mining operations in 2011. However, it was only recently that researchers, under the guidance of archaeologist Harold Berghuis from the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, confirmed the identity and dating of these remains.

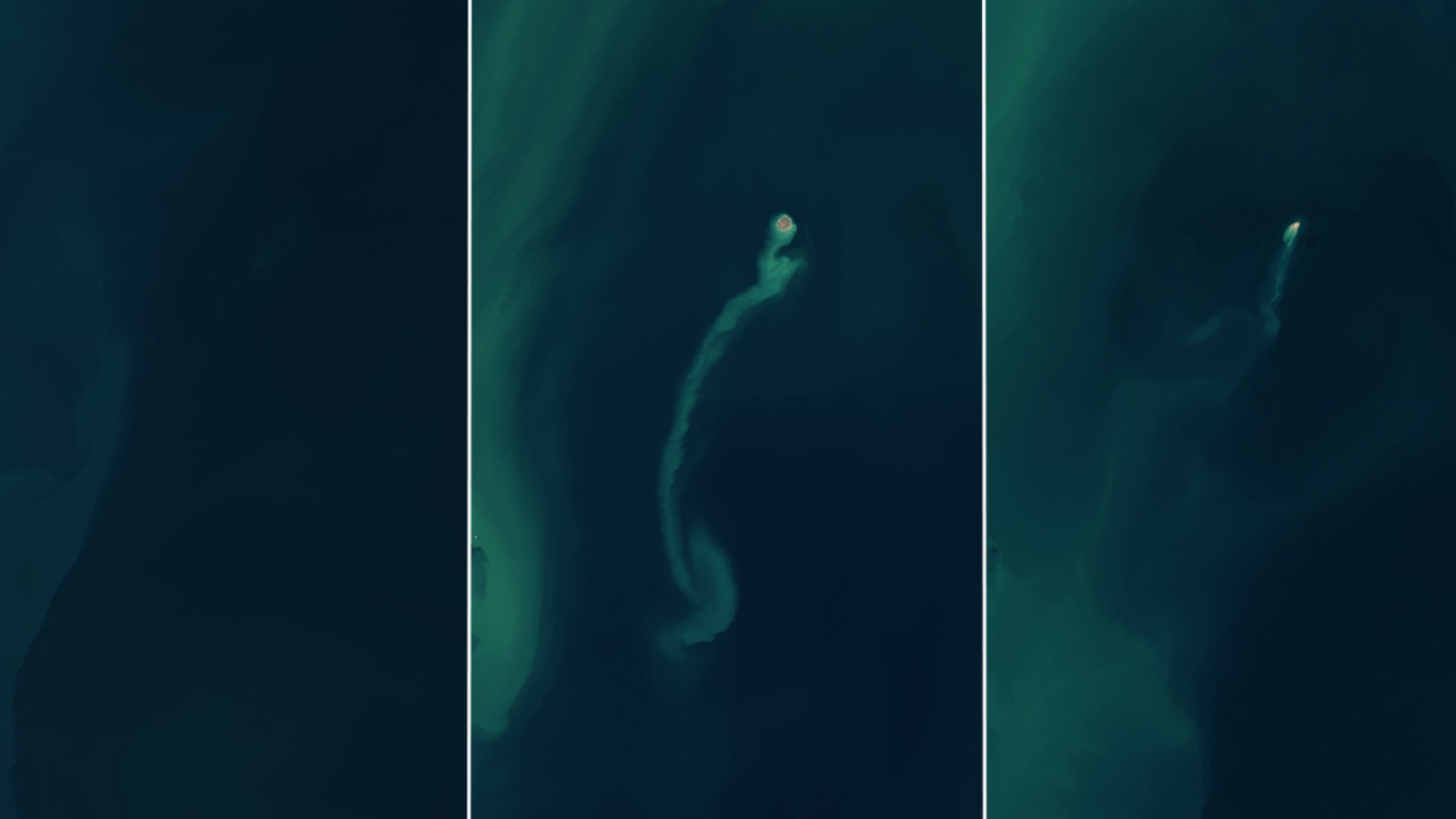

The pivotal moment came when workers near Surabaya, the provincial capital of East Java, were engaged in dredging operations to collect sediment from the sea floor. During these reclamation activities, they encountered fossilized remains that encompassed over 6,000 specimens of vertebrates. The site, remarkably preserved due to the dense accumulation of sand and marine deposits, revealed a breathtaking variety of species, including Komodo dragons, buffalo, deer, and an extinct genus of elephant-like herbivore known as Stegodon, which towered over 13 feet tall.

Among the multitude of fossils were the two human skull fragments: one from the frontal region and the other from the parietal region. Their anatomical features bear a close resemblance to previously discovered Homo erectus fossils from the Sambungmacan site in Java. The dating of these fossils was accomplished using a technique known as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL), which determines the last time sediment was exposed to sunlight. Researchers concluded that the valley containing these fossils dates back between 162,000 and 119,000 years ago.

In addition to the human remains, researchers also uncovered approximately 6,000 animal fossils representing 36 distinct species, further enriching our understanding of the ecosystem that existed in the region. The discovery of these fossils sheds light on a vibrant prehistoric environment that was once home to a rich tapestry of life.

Geological analyses have revealed the buried outlines of an ancient river system, which once formed part of the Solo River, flowing eastward across what is now the Sunda Shelf. Sedimentary records indicate that this river supported a thriving fluvial ecosystem during the late Middle Pleistocene, characterized by a diverse mix of herbivores and predators. Bones and teeth from various deer species have been found scattered throughout the area, providing evidence of a once-abundant fauna.

Researchers believe that this landscape, which was ultimately submerged by rising sea levels between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago, played a crucial role in early human habitation. The melting glaciers that marked the end of the last Ice Age are estimated to have raised ocean levels by over 120 meters, drowning the low-lying plains of Sundaland and severing the connections between the Southeast Asian mainland and its islands.

Notably, the analysis of the animal bones has revealed distinct cut marks, suggesting that early hominins in the region practiced deliberate butchery. These findings imply that the early inhabitants employed tools to hunt and process large animals, a significant indication of their advanced survival strategies. As Berghuis noted, “This period is characterized by great morphological diversity and mobility of hominin populations in the region.”

Additionally, fossils of antelope-like species typically found in open grasslands support the theory that this submerged landscape resembled a savanna rather than a dense jungle. The presence of large herbivores and deer hints at a rich food source that would have been advantageous for both animals and early humans.

The recovery of these skull fragments from the Madura Strait significantly expands our understanding of the geographical range of Homo erectus in Southeast Asia. These early humans are noted for their taller, more upright posture, with longer legs and shorter arms, characteristics that bring them closer in form to modern humans. Their presence in Sundaland provides crucial insights into early human migration and adaptation to the region’s evolving ecosystems.

This unexpected find, initially a chance discovery by sand miners, has evolved into a groundbreaking moment in the ongoing study of early human history in Asia. By integrating archaeological, geological, and paleoenvironmental research methods, scientists are piecing together a lost chapter of human evolution—one that has remained obscured beneath the sea for millennia.