Concerns Rise Over Potential Eruption of Campi Flegrei Supervolcano in Italy

A powerful series of earthquakes has recently struck Campi Flegrei, a massive supervolcano located in Italy, raising new alarms among scientists regarding the potential for a major eruption. This area, known as the Phlegraean Fields, is situated near Naples and has been experiencing heightened seismic activity that could signal deeper geological changes.

In May, the region was rocked by a magnitude 4.4 earthquake, the strongest seismic event recorded there in 40 years. This was not an isolated incident; since then, scientists have documented over 3,000 smaller tremors in the area within a six-month timeframe, significantly exceeding the normal seismic activity for this historically volatile region.

Experts in volcanology explain that eruptions often follow periods of increased earthquake activity, as this is an indication that underground pressure is building. These smaller earthquakes can contribute to the weakening of the rock above the volcano's magma chamber, making it easier for molten rock—or magma—to force its way to the surface. It’s akin to a pressure cooker, where steam builds up over time; if the lid becomes too compromised, it could lead to a dramatic explosion.

Compounding these concerns, geologists have observed a significant uptick in gas emissions from the volcano. The latest reports from Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) indicated that carbon dioxide levels have surged, with daily emissions reaching between 4,000 to 5,000 tons. Increased gas emissions are often interpreted as a sign that magma is moving closer to the surface, raising the pressure further and potentially foreshadowing an eruption.

The INGV has warned that the magma reservoir beneath Campi Flegrei is now located just a few miles below the earth’s surface, which raises alarm bells among scientists. If this pressure continues to escalate, it could lead to an eruption with little to no warning, especially in light of the recent seismic and gas activity.

Christopher R. J. Kilburn, a leading volcanologist at the INGV, emphasized the critical importance of distinguishing between gas emissions caused by magma movement and those resulting from natural rock interactions. This analysis is pivotal for understanding the potential for an impending eruption.

More than four million people reside in the metropolitan area of Naples, making Campi Flegrei a significant threat to public safety. Should an eruption occur, the consequences could be devastating; buildings could be obliterated by lava flows and ash clouds, and fast-moving hot gases could pose lethal risks.

The proximity of the city of Naples and surrounding towns like Pozzuoli places countless lives and homes in jeopardy. Recent research led by Gianmarco Buono, a PhD student at the University of Naples Federico II, reveals that about 80 percent of the carbon dioxide emitted from the Solfatara crater originates directly from magma beneath the Earth's surface. Monitoring this gas release has become crucial, particularly as continuous earthquakes rattle Pozzuoli and nearby areas.

While 20 percent of gas emissions are attributed to natural processes involving hot fluids reacting with underground rocks, which do not necessarily indicate an imminent eruption, the data shows a concerning trend. Scientists are diligently tracking these gas emissions alongside ground swelling and the thousands of small earthquakes, as they serve as key indicators of volcanic unrest.

As magma ascends, it forces gases out, creating internal pressure within the volcano. An accumulation of excessive pressure can lead to fractures in the rock, potentially precipitating an eruption. The term 'Campi Flegrei' translates to 'burning fields', denoting a vast volcanic caldera formed after a massive eruption thousands of years ago that caused a collapse of the ground above the magma chamber. The last known eruption occurred in 1538, and while major eruptions are infrequent, the volcano has exhibited signs of unrest in recent decades.

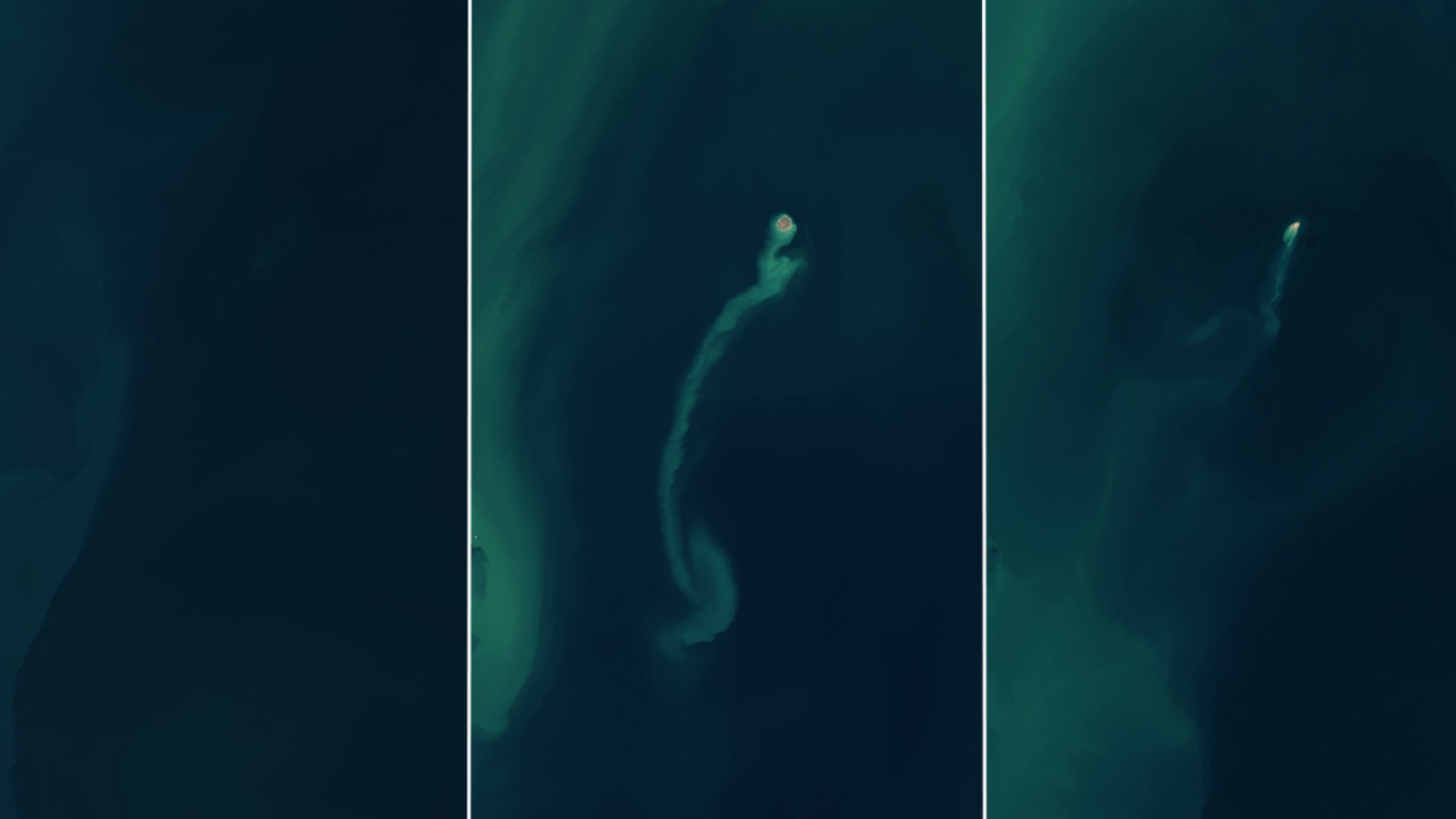

Scientists caution that while precise predictions of eruption timing are impossible, the recent uptick in volcanic activity suggests that the next eruption could be on the horizon. Since 2005, the ground in the Campi Flegrei area has been engaged in a slow process of rising and falling, termed bradyseism, which occurs when magma and gas accumulate underground, pushing the surface upwards or allowing it to sink back down. Notably, in Pozzuoli, the surface has risen approximately 4.7 feet during the current phase of activity.

To better understand the geological responses beneath Campi Flegrei, researchers employed a mechanical failure model commonly utilized in structural engineering. Their findings indicate a shift in the crust from merely bending to cracking, a transition that often precedes volcanic eruptions. The scientists remarked on the clear progression toward a state where rupture becomes increasingly likely.

In response to these rising alarm signals, officials raised the volcano's alert level from green to yellow in 2012, indicating a heightened state of awareness regarding the volcano's potential activity. Authorities have also devised comprehensive evacuation plans for the millions living in the metropolitan area of Naples. However, the efficacy of these plans hinges on swift execution in the event of an impending eruption.

The ramifications of an eruption at Campi Flegrei extend beyond local borders. Approximately 40,000 years ago, the volcano erupted with such intensity that it resulted in one of the most catastrophic volcanic events in Earth's history, leading to significant climate changes worldwide. Should a similar eruption occur today, its impact would be felt globally, with ash clouds potentially blanketing much of Europe, grounding flights, destroying crops, and disrupting power supplies.

The release of volcanic gases could obscure sunlight, leading to years of cooler temperatures and erratic weather patterns that would jeopardize food security worldwide. As scientists continue to monitor this volatile situation, the hope remains that through rigorous research and preparedness, communities can mitigate the risks associated with this formidable natural phenomenon.