Can This Nasal Spray Slow Down Alzheimer's? One Couple is Helping Scientists Find Out

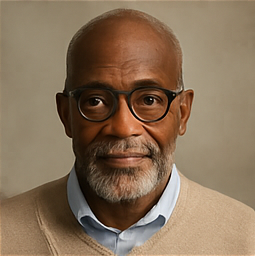

Joe Walsh, a 79-year-old man, sits in a cozy tan recliner at the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment located at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, eagerly awaiting his dose of an experimental treatment. His devoted wife, Karen Walsh, hovers close by, ready to assist with the nasal spray applicator. "One, two, three," a nurse counts down, and with a swift motion, the plunger is pressed down and Joe inhales the spray. This treatment is not just any medication; it is infused with a monoclonal antibody designed specifically to combat inflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Joe Walsh is notably the first individual diagnosed with Alzheimer's to receive this nasal spray, which is also being investigated for its effects on other debilitating conditions, including multiple sclerosis, ALS, and even COVID-19. Researchers have reported promising results, indicating that the spray appears to be successful in reducing the inflammation present in Joe's brain, as noted in the recent findings published in the journal Clinical Nuclear Medicine. Dr. Howard Weiner, a leading neurologist at Mass General Brigham who played a pivotal role in the development of this treatment in collaboration with Tiziana Life Sciences, expresses optimism, stating, "I think this is something special." Yet, the critical question remains: will this decrease in inflammation translate into tangible improvements in Joe's cognitive abilities, including memory and thought processing?

This experimental treatment is part of a broader initiative aimed at discovering new strategies to disrupt the series of biological events in the brain that lead to Alzheimer’s dementia. Currently, there are two FDA-approved medications that focus on eliminating amyloid plaques—accumulations of toxic protein between neurons. Other investigational therapies emphasize targeting tau tangles, another type of protein that amasses inside nerve cells. However, there has been a notable lack of research focusing on addressing inflammation, a symptom of Alzheimer’s that becomes more pronounced as the disease advances.

After Joe completes his inhalation of the experimental drug, Dr. Brahyan Galindo-Mendez, a neurology fellow, administers a cognitive assessment. "Can you tell me your name, please?" Dr. Mendez prompts. After a slight delay, Joe manages to respond, "Joe." The doctor continues, "And who is with you today?" In a poignant moment, Joe’s answer is simply, "We’ll do that," as he struggles to recall the name of his wife, the woman he has shared his life with for 36 years.

Karen Walsh first detected subtle changes in her husband back in 2017. "He was struggling to find the right words to complete a thought or a sentence," she recalls. Concerned, they consulted their primary care physician, who suggested that if Joe was indeed diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, he should consider entering a research study to potentially access the latest treatment options. A referral to a neurologist followed. In 2019, a PET scan confirmed their fears, revealing extensive amyloid plaques in Joe’s brain—a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s was officially made.

"As much as I was in shock," Karen recounts, "the words rang in my head: 'ask for the research.'" With determination, she began to search for clinical trials that might be available. Unfortunately, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to the suspension of numerous research studies and trials. By the time the world began to reopen, Joe’s condition had deteriorated to the point where he was no longer eligible for most ongoing studies.

In late 2024, Karen reached out to Dr. Seth Gale, another neurologist at Mass General Brigham and Harvard Medical School, who assured her that he would actively seek a research study for Joe. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Gale received an inquiry from a colleague who was looking for a patient with moderate Alzheimer’s to participate in a trial involving a monoclonal antibody known as foralumab. This particular antibody was initially being tested on patients with inflammatory diseases, including multiple sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a condition wherein the immune system erroneously targets the protective sheath surrounding nerve fibers, leading to inflammation. Promising results were observed with foralumab in MS patients, who exhibited a reduction in inflammatory responses. Dr. Weiner explains, "It induces regulatory cells that go to the brain and shut down inflammation," which could also be beneficial in treating Alzheimer's-related inflammation, particularly since he has a personal connection to the disease—having lost his mother to Alzheimer's.

While most Alzheimer's treatments focus on eliminating the disease's hallmark features like amyloid plaques and tau tangles, researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of managing the accompanying inflammation as the disease progresses. Dr. Weiner notes, "Once people have Alzheimer's, the inflammation is driving the disease more." Initial tests have shown that the approach worked effectively in animal models that develop Alzheimer-like symptoms.

In order to treat Joe Walsh with foralumab, Dr. Weiner's team had to secure special permission from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through an expanded access program. This program is designed for patients who do not qualify for clinical trials and lack alternative treatment options. Once the FDA granted approval, Joe became the first Alzheimer's patient to receive this innovative treatment. Six months into the treatment, researchers have observed a significant reduction in brain inflammation; however, it is important to note that no medication can reverse the loss of brain cells that have already occurred.

Future cognitive tests will be critical in determining whether Joe’s memory and cognitive function have improved as a result of the treatment. Meanwhile, Karen Walsh has noticed some encouraging signs. Although her husband continues to face challenges with word retrieval, she reports that he has shown greater engagement in social activities. "A couple of guys come pick him up once a month, and they take him out for lunch," she shares. "They sent me a text afterward saying, 'Wow, Joe is really, really laughing and very involved.'"

It appears that Joe himself is content to continue with the treatment. Amidst moments of non sequiturs, he articulately states, "It's easy enough to take it, so I do it, and it feels good." Looking ahead, a clinical trial for foralumab specifically targeting Alzheimer’s disease is set to commence later this year, offering hope to many others facing this challenging diagnosis.