Significant Discovery: 14.6 Million-Year-Old Bee Fossil Unearthed in New Zealand

Deep within the fossil-rich hills near Outram, located on New Zealand’s South Island, paleontologists have made a groundbreaking discovery: the remains of a tiny bee, preserved in volcanic mudstone for 14.6 million years. This remarkable specimen, measuring just over six millimeters in length, is the first of its kind ever found in Zealandia, the largely submerged continent that encompasses New Zealand and its geological surroundings.

This extraordinary finding was detailed in a study published in the scientific journal Zoosystema, which highlights the significance of the location where the fossil was unearthed. The Hindon Maar site is a Miocene-aged volcanic crater lake situated in Otago, renowned for its exceptional preservation of ancient flora and fauna. The discovery of this bee not only enhances our understanding of pollinators in this isolated region but also raises intriguing questions about their evolutionary history.

A Fossil That Doesn’t Fit the Timeline

The fossilized bee, scientifically named Leioproctus (Otagocolletes) barrydonovani, belongs to a genus that includes several species still thriving in New Zealand today. According to Dr. Michael S. Engel from the American Museum of Natural History and Dr. Uwe Kaulfuss of the University of Göttingen, the wing vein patterns of this ancient bee closely resemble those of three modern subgenera of Leioproctus currently found in the region.

However, despite the extensive evolutionary timescale separating the Miocene epoch from today, only 18 species of Leioproctus are endemic to New Zealand. “If the genus had invaded New Zealand before 14.6 million years ago,” the researchers noted, “then it should have had ample time to diversify further or develop specialized relationships with the indigenous flora.” This lack of diversification raises a series of important questions for scientists and ecologists alike.

One plausible theory suggests that the modern species of Leioproctus are not direct descendants of the ancient fossil; instead, they may have arisen from later, separate invasions to the islands. Alternatively, it is conceivable that diversification did occur but was significantly reduced due to extinction events, the causes of which remain a mystery.

Layers of Mystery Beneath the Mudstone

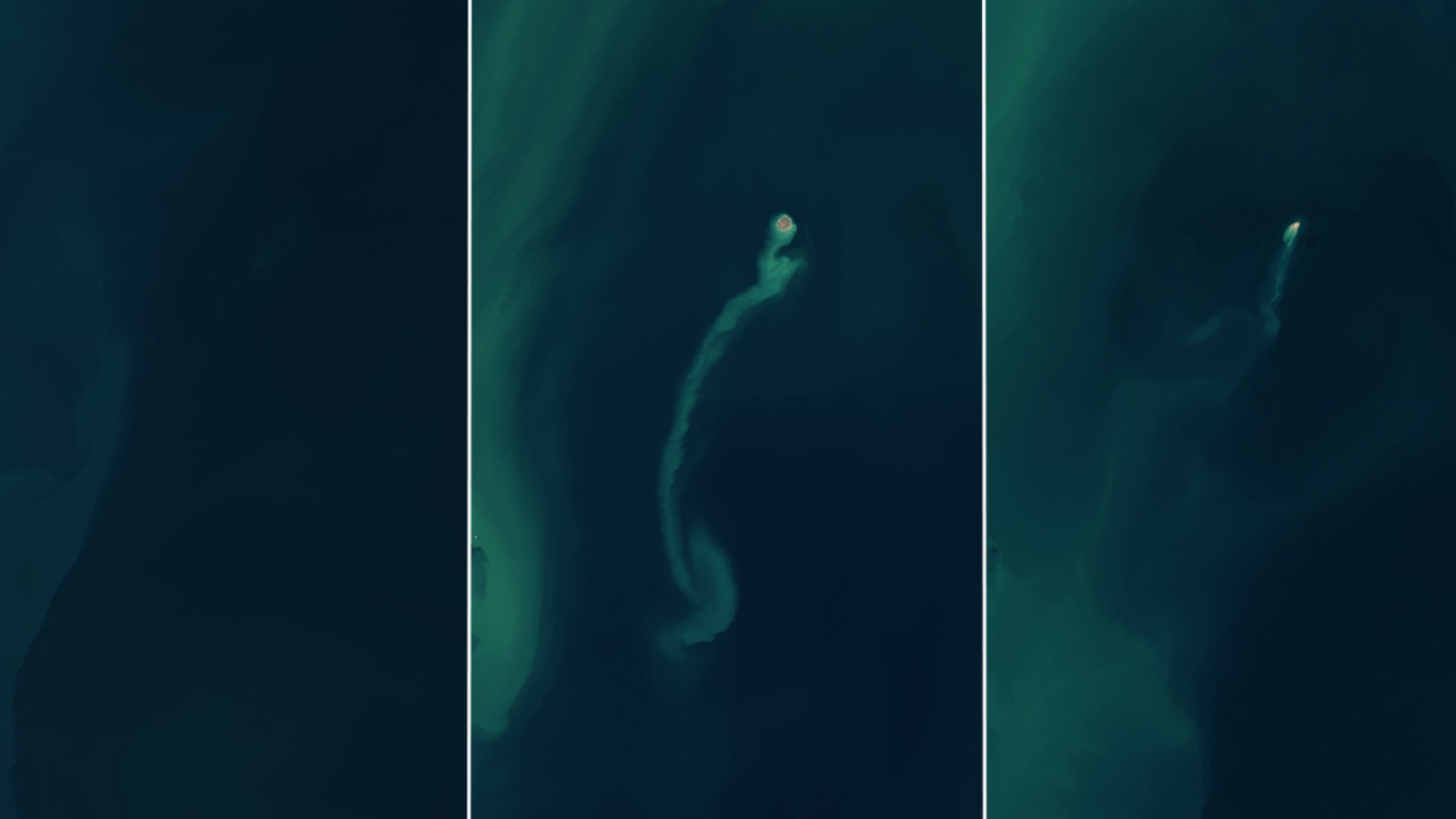

The bee fossil was discovered as a compressed and articulated specimen embedded in dark gray organic mudstone. It is preserved in such a way that researchers can view a nearly complete dorsal perspective of the insect’s body. While the site has yielded various other insect fossils, this is the first bee to emerge from its sedimentary layers.

Accompanying the bee fossil, the researchers recovered 48 fossilized flowers, nearly all belonging to the Araliaceae family, specifically a yet-to-be-described species of Pseudopanax. These flowering trees and shrubs are still widespread throughout New Zealand today. The researchers propose that the fossilized bee might have visited these ancient plants, although this hypothesis remains speculative. Notably, one modern species, Leioproctus pango, is known to collect pollen from Pseudopanax flowers, suggesting a tenuous link between ancient and modern plant-pollinator relationships.

A Rare Glimpse Into Zealandia’s Biota

This fossil offers a rare insight into the biota of Zealandia, a continent that began its separation from the supercontinent Gondwana approximately 80 million years ago. As described by the researchers, “The biota of New Zealand is a mosaic of ancient lineages interspersed among arrays of relative newcomers.” This unique ecological landscape has resulted in a diversity of insects that often reveal intriguing contradictions.

While some insect lineages have evolved in isolation, developing distinctive traits, others, particularly specialized insect pollinators, are noticeably scarce. Although bees are recognized globally for their crucial role as pollinators, they are relatively rare in New Zealand, with only 42 known species, of which 28 are endemic. This limited fossil evidence has posed challenges for researchers trying to determine the timeline for the presence of bees in New Zealand’s ecosystems.

The discovery of Leioproctus barrydonovani marks the first definitive proof that bees were present during the Middle Miocene, yet it also raises more questions than it resolves.

A Puzzle With No Clear Lineage

Complicating matters further is the uncertainty regarding the evolutionary link between the fossil bee and its present-day relatives. “Currently, there are no data to suggest that the three groups of Leioproctus in New Zealand form a monophyletic group,” the scientists write, indicating that these bees could represent multiple, younger invasions rather than a single lineage descending from the Miocene ancestor. If the fossil bee signifies an early arrival, researchers would anticipate finding more evidence of speciation, especially in a landscape as diverse as New Zealand’s. The absence of such evidence points to either evolutionary stagnation or significant ecological pressures that have hindered the bee's development and survival.

As excavations at the Hindon Maar and nearby Foulden Maar fossil sites continue to reveal intricate details about ancient ecosystems, paleontologists remain optimistic. Engel and Kaulfuss express this hope, stating, “The potential to recover in situ pollen is great should additional and more complete bees be uncovered in future excavations.”