New Study Reveals Ancient Humans' Connection to Whales

In a fascinating dive into the depths of our prehistoric past, researchers have uncovered new insights about the relationship between early humans and whales. Although modern whale populations are drastically diminished, evidence suggests that these majestic marine mammals flourished thousands of years ago. Early human communities living along the coasts relied heavily on whales, not only as a vital source of food but also as materials for tools and implements. Whale bones were transformed into essential tools, including harpoons, which were then used to hunt even more whales.

Determining the exact timeline of when humans began utilizing whales poses a challenge for scientists today. Many of the coastal sites where early humans lived have either been submerged under the ocean or eroded away over millennia. As a result, instead of discovering intact archaeological sites by the sea, researchers often find whale bones and tools crafted from whale materials in caves located far inland. These artifacts were carried by ancient peoples who ventured into these caves thousands of years ago.

A recent study led by ICTA-UAB, CNRS, and the University of British Columbia (UBC) has shed light on this ancient relationship, revealing that humans began crafting tools from whale bones approximately 20,000 years ago. This groundbreaking research establishes new links between Paleolithic coastal communities and these ocean giants, providing a deeper understanding of early human life.

The study involved an extensive analysis of over 170 bone samples collected from various locations across Spain and southwestern France. Among these samples were 83 shaped tools and 90 unworked bone fragments, with the tools primarily serving as weapons. Notably, this discovery represents the oldest evidence of tool-making from whale bones ever documented.

Jean-Marc Pétillon, the lead researcher, remarked, “Our study reveals that the bones came from at least five species of large whales, the oldest of which date to approximately 19,000–20,000 years ago. These represent some of the earliest known evidence of humans using whale remains as tools.”

The researchers employed advanced techniques, including mass spectrometry and radiocarbon dating, to analyze the samples. Their key method, ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry), enabled them to differentiate between various whale species, identifying fragments from fin, sperm, gray, blue, and right/bowhead whales. These species, known for foraging offshore or swimming close to the coastlines, provided varying degrees of access for ancient human hunters.

Sperm whale bones were particularly prized among the tool-making materials. This preference likely stems from the bone’s straight, dense structure that is ideal for crafting into long, pointed weapon tips. Additionally, researchers found carved sperm whale teeth, suggesting that they held both symbolic and practical uses for these early communities.

Another pivotal aspect of the research involved stable isotope analysis, revealing that ancient whales exhibited different feeding behaviors compared to their modern counterparts. For instance, sperm whales demonstrated high nitrogen values indicative of a diet rich in squid, while fin whales showed lower values consistent with a krill-based diet. Meanwhile, gray whales exhibited distinct carbon signatures pointing to bottom-feeding behaviors near the shore.

The research findings also highlighted the significant changes in marine ecosystems over time. While certain feeding patterns align with those of contemporary whales, the higher isotope values suggest that ancient marine life offered broader or richer prey availability in the past. For instance, at the Santa Catalina Cave, large, unworked whale bones had been transported inland, despite the cave’s elevation of 70 meters above sea level and several kilometers from the coast. While these bones were not fashioned into tools, many displayed signs of percussion marks, indicating they were intentionally broken.

Researchers suspect this indicates that early humans were extracting fat or oil from the bones, similar to how they would have harvested marrow from terrestrial animals. The surrounding archaeological layers also revealed evidence of hearths and other fire-related features, suggesting that the site had been frequently used for fire-related activities. Although the whale bones showed minimal signs of burning, they likely served as a valuable reserve of fat, either for food, warmth, or as fuel for future fires.

This behavior exemplifies the deep importance of whales beyond simply providing bones for tools; they represented a vital resource for these early peoples, especially during periods when other materials were scarce. It highlights the ingenuity and adaptability of coastal communities in managing marine resources.

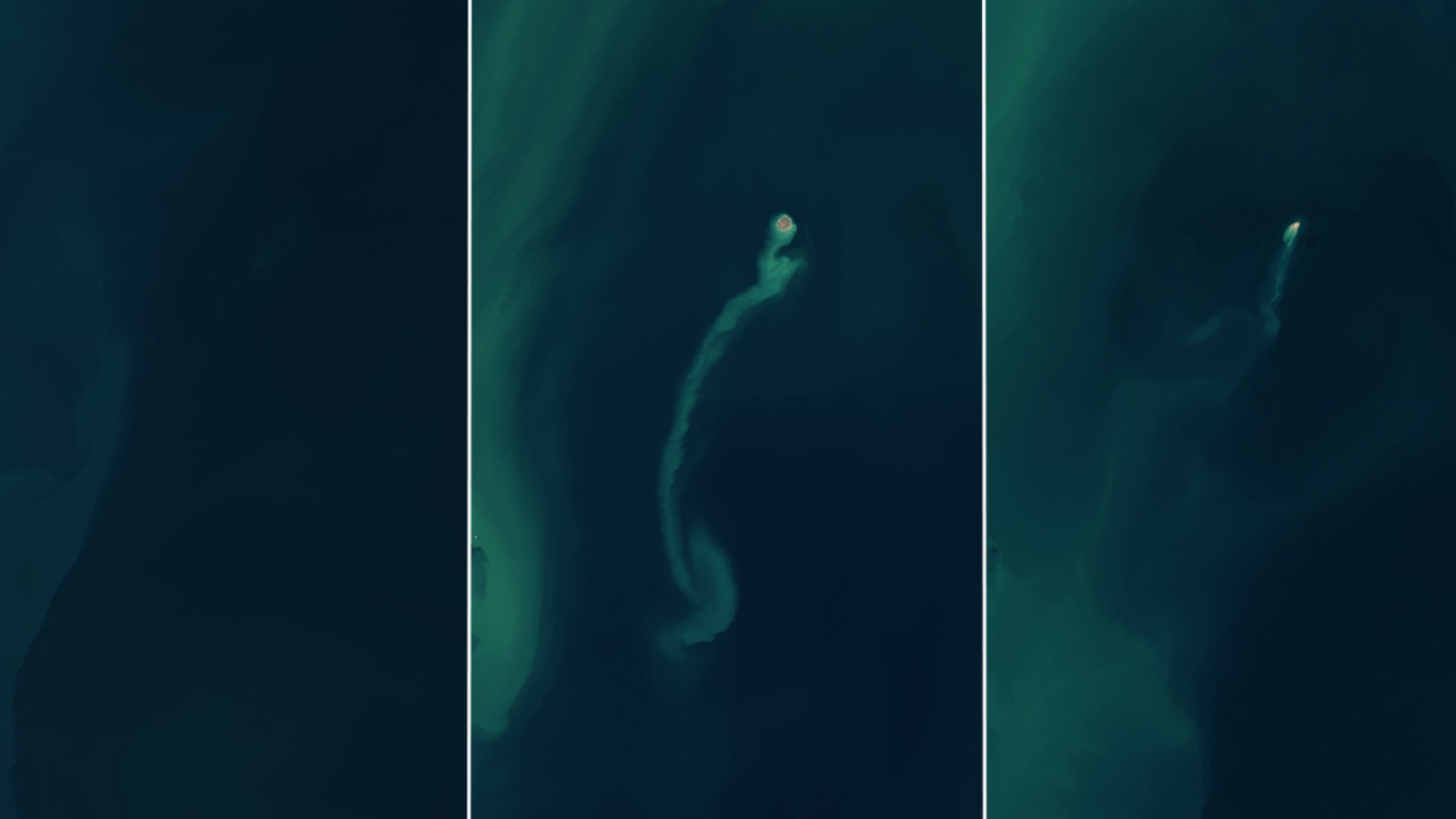

During the Magdalenian period, the Bay of Biscay likely resembled frigid Arctic waters, with seasonal sea ice and abundant marine life making it an attractive habitat for both whales and early humans. The presence of whale bones points to not only tool usage but also the broader ecological network that these early humans depended upon. While hunting whales may not have been a widespread practice, the evidence suggests that these ancient communities had a keen understanding of whale behaviors, making use of natural strandings and seasonal appearances.

By around 16,000 years ago, the use of whale bones as tools saw a decline. This change was not necessarily due to a lack of whales or a decline in skill. Instead, shifting cultural habits or disruptions in coastal exchange networks might have influenced resource utilization. Nevertheless, the discovery of whale bones deep inland underscores the extent to which marine life influenced the lifestyles and mobility of these ancient communities. Whales transcended their role as mere sea creatures; they were integral to the survival and innovation of Paleolithic peoples.

This research not only provides a rare glimpse into prehistoric life but also emphasizes the resourcefulness and attentiveness of our ancestors, illustrating how marine ecosystems shaped their existence. The findings of this study are now published in the esteemed journal Nature Communications.