Ancient Dinosaur Footprints Rediscovered: A Bridge Between Continents

In what is now northern Cameroon, a remarkable imprint was made in the wet river mud—three clawed toes, each measuring the length of a human hand. This striking evidence of prehistoric life, preserved in the earth, captured a fleeting moment in time. As the waters receded, silt drifted over the print, safeguarding it for millions of years until modern-day scientists could uncover its significance.

Fast forward 120 million years, and this fossilized step has provided researchers with crucial insights into the world that existed in the Early Cretaceous period. During this era, the land that is now Cameroon was physically connected to the northeastern edge of Brazil. At that time, there was no Atlantic Ocean separating these two landmasses; instead, a sprawling, low-lying swamp intertwined the regions.

The landscape was filled with long-necked herbivores that leisurely traversed the reed beds, while sharp-toothed predators stalked their prey. Each footfall left an imprint in the clay, documenting the dynamic life that once thrived there.

This ancient environment is referred to by geologists as Gondwana, the great southern supercontinent that had only recently started to split from Pangea, the original supercontinent. Approximately 140 million years ago, tectonic forces began to pull Gondwana apart, creating rifts that would eventually give rise to the South Atlantic Ocean.

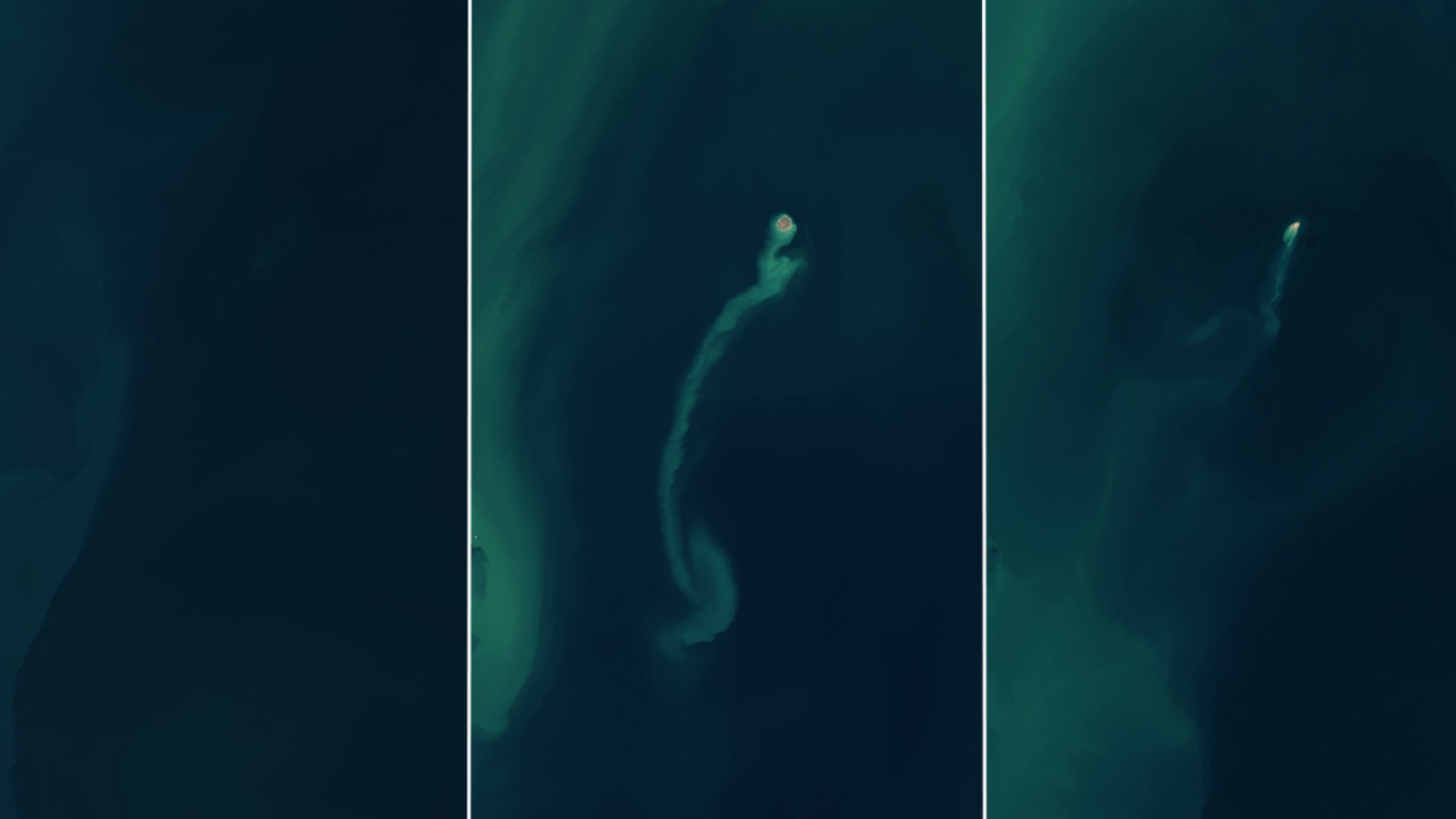

Even as magma pushed upwards offshore, rivers continued to flow across what would soon become the ocean floor, allowing diverse wildlife to roam freely between the two continents. Two key locations where these paths are now exposed are the Koum Basin in Cameroon and the Borborema region in Brazil, which lie over 3,700 miles apart.

A recent study led by paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs of Southern Methodist University (SMU) has illuminated the connection between these two significant sites. Jacobs and his international team meticulously cataloged more than 260 dinosaur tracks discovered in both the Koum Basin and the Sousa Basin in Brazil. They corroborated that not only were these footprints similar in age, but they also shared striking similarities in geological and plate tectonic contexts.

“In terms of age, these footprints were similar,” Jacobs stated. “In their geological and plate tectonic contexts, they were also similar. In terms of their shapes, they are almost identical.” These two sites, which once stood side by side, now preserve a remarkable phenomenon known as the Dinosaur Dispersal Corridor.

Most of the tracks found belong to three-toed theropods, the swift carnivores of their time. A small number of tracks from sauropods and ornithopods were also cataloged, suggesting that herds of plant-eaters were moving through the same wetlands. The sediments surrounding these tracks also contained pollen from the same era, approximately 120 million years ago, further reinforcing the idea of a shared environment on both sides of the Atlantic.

Jacobs elaborated, “One of the youngest and narrowest geological connections between Africa and South America was the elbow of northeastern Brazil, nestled against what is now the coast of Cameroon along the Gulf of Guinea.” This narrow stretch of land allowed animals from either continent the opportunity to migrate across it.

These footprints capture a fleeting moment when the land bridge was still intact yet fragile, providing a snapshot just before the continents drifted apart permanently. River valleys acted as natural highways, with their floodplains offering essential resources such as water and vegetation, as well as a soft ground that perfectly preserved these ancient prints.

Jacobs noted, “Rivers flowed and lakes formed in the basins. Plants fed the herbivores and supported a food chain.” The muddy sediments left by these rivers and lakes are rich with dinosaur footprints, showcasing that these river valleys once served as vital routes for life to traverse the continents 120 million years ago.

With each rainy season, new tracks layered upon the old, creating an intricate narrative of migration and movement. Beyond footprints, fossil evidence within nearby basins has unveiled the existence of crocodilians, turtles, fish, and even early mammals, such as Abelodon abeli, a curious tooth-shaped creature hinting at the evolutionary roots of modern mammals.

Each new discovery fills in the gaps of understanding regarding how life adapted during a time of significant geological upheaval. The Koum and Babouri-Figuil basins are half-graben structures—troughs formed when the earth's crust stretches and drops along faults. While similar basins are found along both coasts of the South Atlantic, few are as rich in terrestrial fossils as these.

Consequently, northern Cameroon has become a focal point for researchers tracing the journeys of dinosaurs across Gondwana. The first significant discoveries were made in the 1980s during the multinational PIRCAOC project, and ongoing excavations continue to yield surprising finds, despite the region's remote location.

In Brazil, the matching tracks are preserved within ancient red siltstones that once lined lagoons, with their fine grain allowing for the remarkable preservation of claw imprints and skin traces. Together, these African and South American sites validate that dinosaurs roamed across a unified landmass long after Pangea began to unravel, utilizing the same river corridors that would later be transformed beneath the Atlantic Ocean.

Understanding these tracks is crucial for modern science. Researchers' studies of the dispersed footprints enhance computer models that reconstruct the movements of continents, aiding predictions regarding the locations of oil, minerals, and groundwater today.

Additionally, these studies emphasize how wildlife migration routes shift in response to climatic and geographical changes, imparting significant lessons for today's animals facing habitat fragmentation.

Visitors can now traverse marked paths to view several of the dinosaur footprints in Cameroon, stepping where theropods once hunted. Local guides describe the site as a “story written in stone,” indicative of the deeply interconnected narratives of ancient life.

As researchers continue to scan, map, and compare each trackway, the story of these tracks is far from complete. Future excavations may unveil additional corridors, demonstrating that prehistoric migrations were as intricate and widespread as the journeys undertaken by animals in contemporary times.

These footprints serve as a poignant reminder of the slow yet powerful movement of continents, capable of reshaping oceans, climates, and the migratory pathways available to life. By interpreting the mudstone records of Cameroon and Brazil, scientists gain valuable insights into how ancient creatures adapted to a changing world—walking, feeding, and multiplying across a supercontinent that no longer exists, yet whose legacy endures beneath our feet.

The comprehensive study that sheds light on this fascinating topic has been published by the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–