Jafar Panahi: The Fearless Iranian Filmmaker Returns to Sydney with His Award-Winning Film

Jafar Panahi, the acclaimed Iranian filmmaker, is a symbol of resilience and creativity, having secured top awards at the world's foremost film festivals: Cannes, Venice, and Berlin. His latest film, It Was Just an Accident, achieved the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2025, making waves in both the cinematic and political realms.

Initially, the news of Panahi’s visit to Sydney for the Australian premiere of It Was Just an Accident was shrouded in secrecy. Festival organizers opted for discretion, not even revealing his name until the last minute. This cautious approach stemmed from the filmmaker's tumultuous relationship with the Iranian government, which has subjected him to imprisonment and house arrest due to his daring exploration of social themes through film.

Having been banned from filmmaking in Iran, Panahi’s works often feature non-professional actors and delve into the complex social fabric of the theocratic republic. His previous films have tackled significant issues such as women's rights and personal freedoms, reflecting the struggles faced by many citizens in Iran.

Recently, Panahi was granted permission to travel abroad, a rare opportunity that coincided with his acceptance of the Palme d'Or for his latest work. This moment of détente highlights the global respect he commands, making it a calculated risk for the Sydney Film Festival to reveal his attendance.

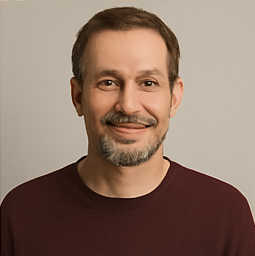

At the Sydney Film Festival, Panahi received an enthusiastic welcome, appearing on stage at the State Theatre to the applause of an appreciative audience. Two days later, I had the chance to sit down with him, facilitated by a translator, at the Park Royal Darling Harbour. Dressed in his signature black attire and sunglasses, Panahi spoke passionately about his reasons for continuing to create despite the risks involved. “When you are in pain over something and it is tickling at you, you say, ‘I must make a movie,’” he explained. This profound commitment to storytelling stems from his belief that art should resonate with the real struggles of society.

Panahi elaborated on the theme of *accidents* in his work, suggesting that even seemingly trivial events can carry a weighty moral obligation. He expressed a keen sense of duty to depict the realities of life in Iran, stating, “The changes I feature are borne out of society.” His evolution as a filmmaker can be traced back to his mentorship under Iranian New Wave pioneer Abbas Kiarostami, who instilled in him the importance of using cinema as a vehicle for social commentary.

His filmography includes The Circle (2000), which confronts issues surrounding access to abortion and sex work, and Offside (2006), a tale of young women defying the ban on attending soccer matches. Panahi’s commitment to addressing women's rights in Iran remains unwavering, especially in light of recent protests against the government following the tragic death of Mahsa Amini, an event that sparked widespread civil unrest.

During his recent imprisonment, Panahi was shielded from the outside world, making it difficult to grasp the realities of the protests unfolding across Iran. He shared a harrowing experience where a medical issue necessitated a visit to a specialist, allowing him a fleeting glimpse of the demonstrations. “They didn't want me to see anything, but I could, through the front windshield,” he recounted, revealing his awe at the societal changes taking place before his eyes. “I could see that the city has already changed.”

Now that he has regained his freedom, Panahi feels compelled to portray the truth of the Iranian experience on screen. “I cannot make another film in which all of the women on the street are wearing a hijab. I would be telling a lie,” he stated, underscoring his dedication to authenticity in storytelling. His films resonate with audiences worldwide, and the Sydney Film Festival has embraced this connection, featuring a retrospective of his works alongside the debut of It Was Just an Accident.

This new film draws inspiration from Panahi’s experiences of interrogation during his first imprisonment. It explores complex moral questions: How would one react when confronted by their interrogator? Would they seek answers, show compassion, or exact revenge? In reflecting on the personal toll of his circumstances, Panahi expressed gratitude for the ability to engage with audiences through his films. “The Iranian government put a distance between us and the viewers,” he lamented. “But now I can sit with them and see which part of the movie works and which is not OK.”

Despite the difficulties he faces, Panahi remains steadfast in his love for his homeland. “Life in Iran is not difficult for me. Life outside is,” he emphasized, rejecting the notion of leaving his country for a life abroad. His time spent editing It Was Just an Accident in France felt like an eternity, and he longed to return home, underscoring his connection to his roots.

With the Australian premiere of It Was Just an Accident at the Sydney Film Festival on May 13, alongside a celebration of his cinematic contributions, Jafar Panahi continues to inspire hope and provoke thought through his courageous storytelling.