Rediscovery of Federico García Lorca's Hidden Sonnets: A Cultural Revelation

In the autumn of 1983, a remarkable literary event occurred when a select group of readers received an unusual envelope. Inside this envelope was a slim, red booklet containing a collection of sonnets that had been kept under wraps for nearly five decades. These poignant verses were crafted by none other than Federico García Lorca, the renowned Spanish poet, whose legacy looms large over 20th-century literature.

Despite the anonymity of the initiative that brought this booklet to light, its purpose was unmistakably clear from the dedication found on the last page. It read: “This first edition of the Sonnets of Dark Love is being published to remember the passion of the man who wrote them.” What followed was a tumultuous journey of love, anguish, and the struggle for artistic expression in a country grappling with the aftermath of civil war.

Within the pages of this booklet, readers found a collection of deeply homoerotic and emotionally charged poetry, penned by Lorca shortly before his untimely death during the Spanish Civil War. The poems, steeped in longing and despair, invite a lover to “drink spilt blood from the honey thigh” and express heart-wrenching vulnerability, as seen in lines that lament: “I suffered you, I clawed my veins/Tiger and dove over your waist/In a duel of bites and lilies.” Such evocative imagery reveals the depth of Lorca's emotional landscape and his unflinching exploration of desire.

The story behind the booklet’s initial publication is as fascinating as the poetry itself. In an effort to compel Lorca’s family to release these works, an unidentified group of intellectuals managed to procure the poems, which had been kept hidden due to the family’s fears that their publication would tarnish Lorca’s legacy and provoke societal backlash. These literary activists printed the poems and disseminated them to 250 notable figures in literature and journalism, ensuring that the sonnets would not remain obscured.

Eventually, the strategy bore fruit. Just a year later, Lorca’s family agreed to publish the complete set of sonnets. However, their choice to collaborate with the right-leaning newspaper ABC raised eyebrows, particularly when the publication consistently refrained from using the term “homosexual” in its coverage of the poems. This omission highlighted the era’s pervasive cultural taboos surrounding sexuality and the challenges confronted by LGBTQ+ individuals.

Henrique Alvarellos, who currently oversees the newly released facsimile edition of the original booklet, stated, “What we’re talking about here is the last poems written by Lorca that appeared in a book that came out 50 years later.” Alvarellos further elucidated the cultural context of the time, reflecting on the lingering remnants of old prejudices that haunted Spanish society, stating, “You can imagine that the publication of this edition – initially clandestinely – had an enormous impact on the country back then.”

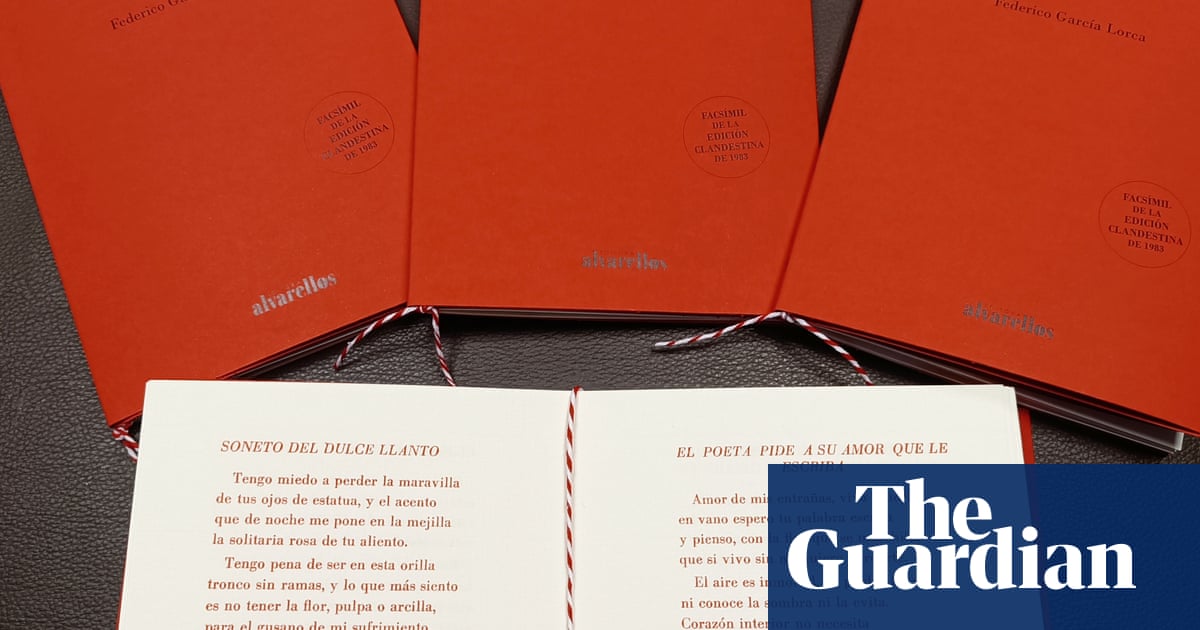

The journey to produce this new edition began when Alvarellos received a copy of the original red booklet from an anonymous source. The rarity of these booklets has significantly increased over time, with current market values reaching around €5,000 each. The new edition aims for authenticity, with Alvarellos ensuring that it mirrors the original in both texture and structure, declaring it “a 100% faithful facsimile edition of the original.”

In addition to the poems, this new edition also includes touching remarks from two fellow poets who were privileged to hear Lorca’s sonnets recited aloud. Chilean poet Pablo Neruda reminisced about the last time he was with Lorca, recalling how he was captivated as Lorca shared several sonnets with him in hushed tones. “All I could do was stare at him and say: ‘What a heart. So much love and so much suffering!’” he reflected, capturing the profound emotional depth that Lorca conveyed.

Ian Gibson, a biographer of Lorca and one of the original recipients of the clandestine booklet, admitted that even he remains in the dark regarding the identities of those behind its initial publication. He recounted a conversation with poet Vicente Aleixandre, who similarly expressed disbelief over the absence of the term “homosexual” in the coverage of the sonnets, despite their explicit content. “It was incredible,” Gibson said. “The grammar – the adjectives and so on – make it explicit that he’s talking about homosexual love.”

For many, the parallels between Lorca’s struggle for acceptance and those of other literary figures, such as Oscar Wilde, are striking. Gibson noted, “It was the love that dared not speak its name. These sonnets are very intimate. They are quite explicitly about homosexual love and the anguish involved.” The title itself, Amor Oscuro, encapsulates the essence of a love that is both difficult and profound, a search for illumination in a world that often remains shrouded in darkness.