Ice Age 'Puppies' Discovered in Siberia: New Insights Reveal They Were Actually Wolf Cubs

NOVOSIBIRSK - In a remarkable discovery, two well-preserved ice age specimens referred to as the “Tumat Puppies” have been found in Northern Siberia, but recent research suggests that these creatures may not belong to the dog family at all. These unique remains, which are still covered in fur and have been naturally preserved in ice for thousands of years, provide fascinating insights into the life of ice age animals. The two puppies were discovered with remnants of their last meal still in their stomachs, including meat from a woolly rhinoceros along with feathers from a small bird known as a wagtail. Initially believed to be early domesticated dogs or tamed wolves that lived in proximity to humans, further investigation into the animals' remains has led researchers to propose that they were actually two-month-old wolf pups that show no evidence of having interacted with humans.

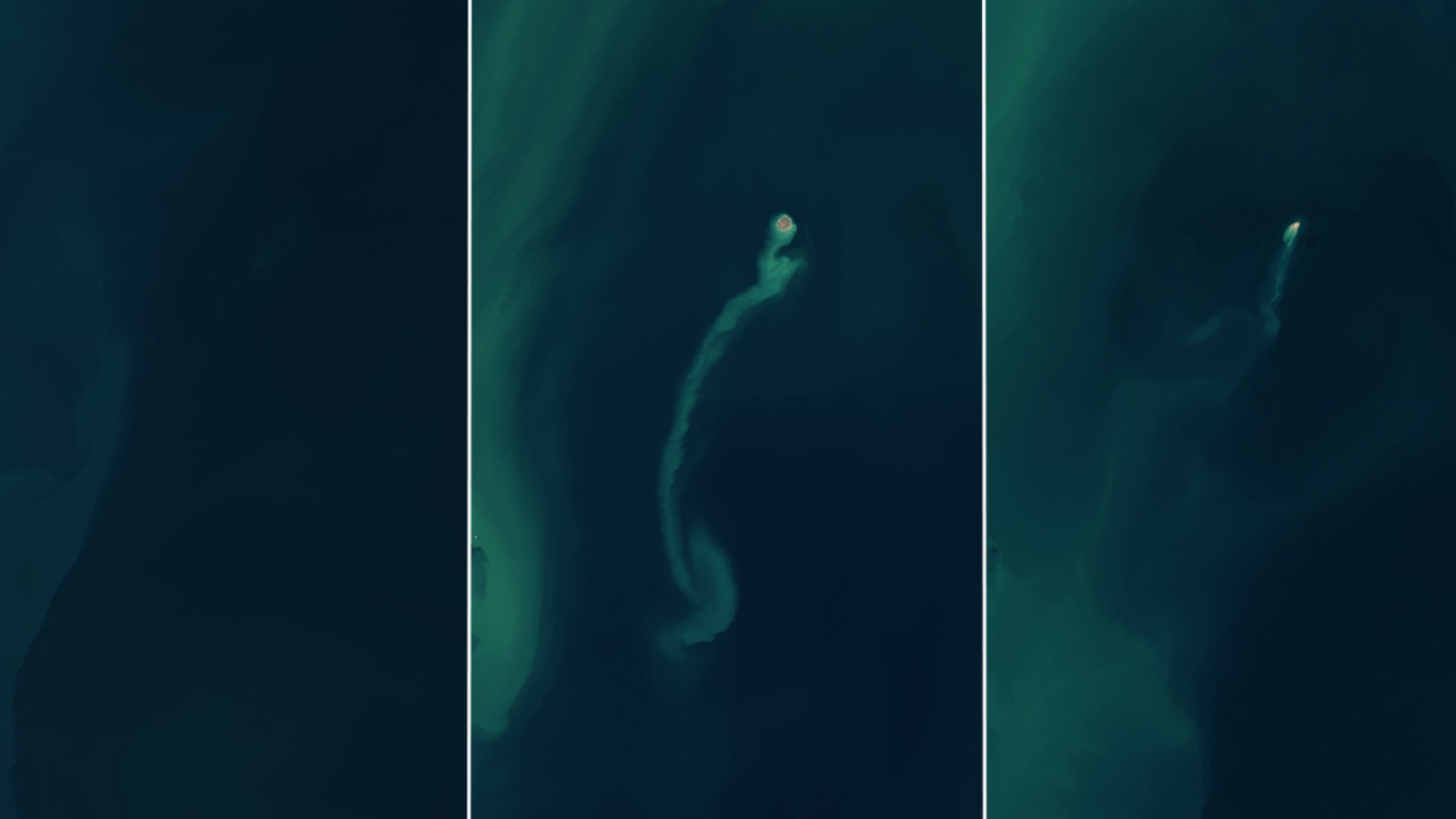

The findings, published Thursday in the esteemed journal Quaternary Research, indicate that these creatures lived near a site where humans butchered mammoths, as their remains were uncovered close to woolly mammoth bones that had been both burned and cut by ancient humans. Researchers utilized genetic data derived from the gut contents and chemical signatures present in the bones, teeth, and soft tissues of the puppies to arrive at this conclusion. The two mummified pups, believed to be siblings, did not exhibit any signs of injury or attack, suggesting that they perished suddenly when their underground den collapsed, potentially due to a landslide, over 14,000 years ago.

Lead study author Anne Kathrine Wiborg Runge, who was previously a doctoral student at the University of York and the University of Copenhagen, expressed her amazement at the findings. “It was incredible to find two sisters from this era so well preserved, but even more incredible that we can now tell so much of their story, down to the last meal that they ate,” Runge stated in an official release. She acknowledged that while many might be disappointed to learn that these animals are likely wolves, not early domesticated dogs, their discovery has significantly contributed to our understanding of the environment during the ice age, as well as the lifestyle of these ancient creatures. Remarkably, wolves from over 14,000 years ago share a striking resemblance to contemporary wolves.

This research emphasizes the challenges scientists face when attempting to pinpoint when dogs, widely recognized as the first domesticated animal, became an integral part of human society. The Tumat Puppies were found separately at the Syalakh site, approximately 25 miles (40 kilometers) away from the nearest village of Tumat, with one being uncovered in 2011 and the other in 2015. Analysis indicates that these puppies are approximately 14,046 to 14,965 years old. Dr. Nathan Wales, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of York in England and one of the study's coauthors, explained, “Hair, skin, claws, and entire stomach contents can survive eons under the right conditions.” Runge noted how remarkable it is that archaeologists managed to discover the second Tumat Puppy several years after the first, highlighting the rarity of finding two such well-preserved specimens that turn out to be siblings.

Moreover, the diet of the pups sheds light on their role within the ecosystem. Similar to modern wolves, they consumed both meat and plants. The presence of woolly rhinoceros skin in one pup’s stomach provides evidence of their diet, suggesting that they were fed by their pack. The skin, bearing light-colored fur, was partially digested, which implies that the pups were resting in their den and likely died shortly after consuming their last meal. Runge pointed out that the color of the woolly rhino fur corresponds with that of a calf, suggesting that the pack of adult wolves hunted the calf and brought it back to the den to feed the pups.

Wales further commented on the implications of their findings, stating, “The hunting of an animal as large as a woolly rhinoceros, even a baby one, suggests that these wolves are perhaps bigger than the wolves we see today.” The researchers also examined tiny plant remains that were fossilized in the cubs’ stomachs, revealing that these wolves thrived in a dry, somewhat mild environment capable of supporting a diverse range of vegetation, including prairie grasses, willows, and shrub leaves.