Discovery of Ancient Wolf Cubs Reveals Insights into Early Canine Evolution

Two small cubs that perished over 14,000 years ago were once believed to be early domesticated dogs, but groundbreaking new findings have confirmed that these so-called “puppies” were actually wolf cubs. Their final repose, curled up in their den, has transformed them into remarkable scientific time capsules, providing vital insights into their lives and the environment they inhabited.

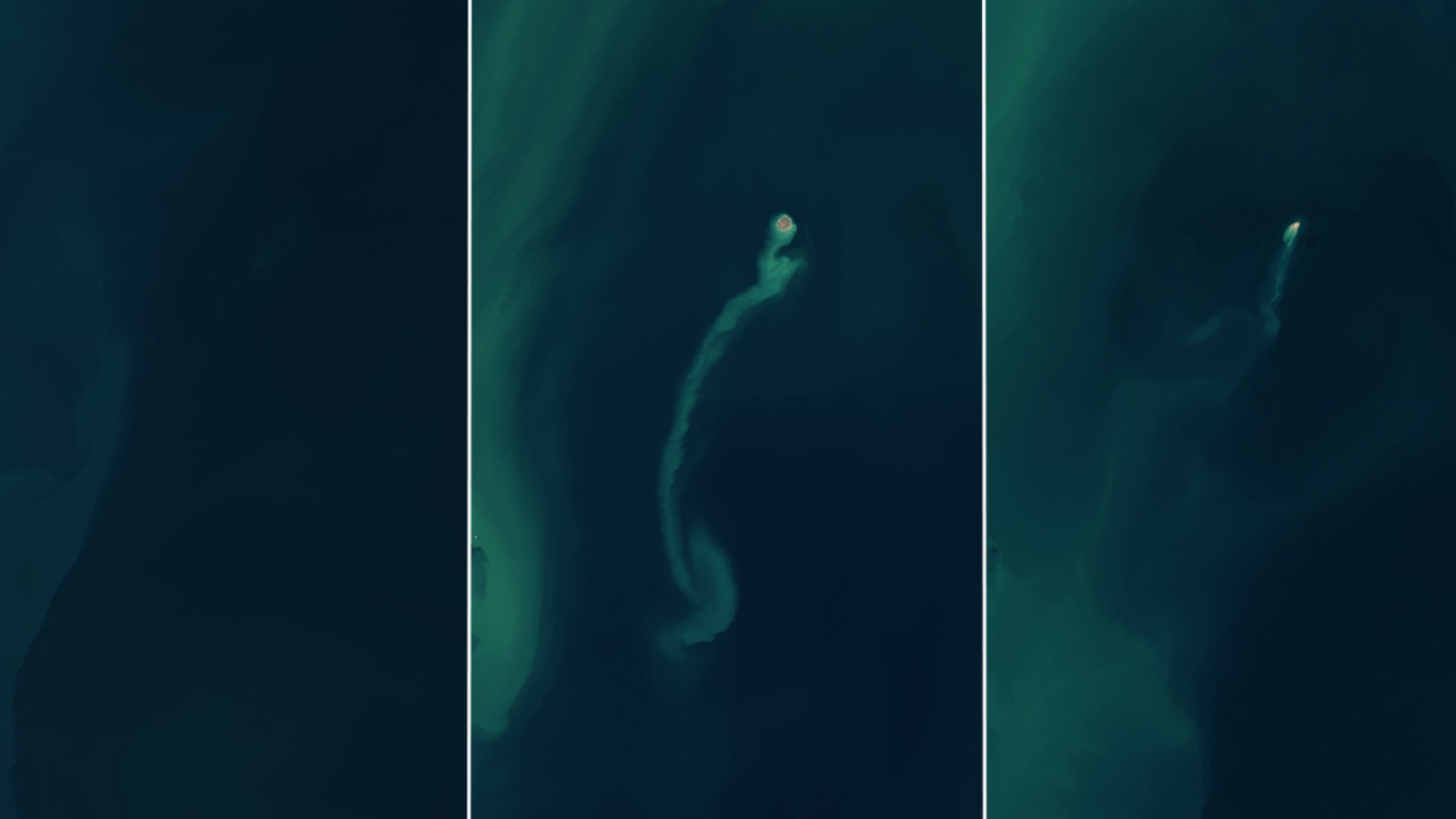

The frozen remains of the cubs were discovered in northern Siberia, approximately 40 kilometers (25 miles) from the village of Tumat. One cub was unearthed in 2011, while the other was found in 2015, both at a site now known as Syalakh. They were interred deep within layers of permafrost, preserved alongside mammoth bones that bore signs of having been burned and butchered.

This unusual combination of human activity and the well-preserved remains of the cubs led to early speculation about their origin. Some researchers posited that the cubs might have been early dogs, potentially living alongside humans or scavenging near human settlements. Compounding this theory was the discovery of black fur on the cubs, a trait previously thought to be exclusive to domesticated dogs.

However, new research conducted by the University of York has illuminated a different narrative. Scientists meticulously analyzed genetic material extracted from the cubs’ stomachs and examined chemical signals found in their bones, teeth, and tissue. The compelling data indicated that these animals were not early domesticated dogs at all, but rather wolves that had thrived in the wild during the Pleistocene epoch.

Interestingly, the cubs were approximately two months old and still dependent on their mother for nursing. Nevertheless, they were also consuming solid food, which included meat from a woolly rhinoceros and, in one instance, the remains of a small bird known as a wagtail. The discovery of undigested rhino skin in one cub's stomach provided a clue about their final meal, indicating how recently they had eaten and the abruptness of their untimely demise.

“It was incredible to find two sisters from this era so well preserved, but even more incredible that we can now tell so much of their story, down to the last meal that they ate,” stated Anne Kathrine Runge, a researcher from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology.

Researchers theorize that the cubs showed no signs of injury or attack. Instead, it is believed that they were resting in their den, potentially after a meal, when a landslide or collapse occurred, trapping them. “While many will be disappointed that these animals are almost certainly wolves and not early domesticated dogs, they have helped us get closer to understanding the environment at that time and how remarkably similar wolves from more than 14,000 years ago are to modern-day wolves,” explained Runge.

Additionally, she noted that the revelation complicates the mystery of how dogs evolved from their wolf ancestors. The presence of black fur color, once considered a significant clue in tracing the evolution of domestic dogs, may in fact be misleading, as it is found in this wolf population that is not directly related to domestic dogs.

The analysis of the cubs’ stomach contents revealed fossilized remnants of various plants, including prairie grasses, willow twigs, and leaves from Dryas shrubs. This finding indicates that they inhabited a diverse and rich ecosystem teeming with edible plants and animals. Despite their proximity to mammoth bones, there was no evidence suggesting the cubs consumed mammoth meat. Instead, researchers found that the clear evidence of woolly rhinoceros in their diet points to a fascinating hunting behavior.

While a fully grown woolly rhinoceros would be far too large for a cub—or even an adult wolf—to take down, scientists suspect that the pack likely hunted a young calf, which was then shared with the cubs. This raises intriguing questions about the physical capabilities of ancient wolves. Were they larger and more powerful than today’s gray wolves?

Dr. Nathan Wales, also from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology, explained that gray wolves have existed as a species for hundreds of thousands of years, as evidenced by skeletal remains from various paleontological sites. Genetic testing of some of these remains has been conducted to track changes in wolf populations over time. The soft tissues preserved in the Tumat cubs offer another fascinating avenue for exploring the evolutionary lineage of wolves.

“We can see that their diets were varied, consisting of both animal meat and plant life, much like that of modern wolves,” he stated. “Moreover, we gain insight into their breeding behaviors as well. These two cubs were sisters and were likely being cared for in a den by their pack — behaviors that are consistent with how wolves raise their young today.”

It is common for modern wolves to have larger litters than just two cubs, which raises the possibility that the Tumat cubs had siblings who may have escaped a similar fate. Perhaps more of their littermates remain hidden within the permafrost, waiting to be discovered.

Dr. Wales further elaborated on the significance of the woolly rhinoceros remains found in the cubs’ stomachs. “The hunting of such a large animal, even a baby one, suggests that these wolves might have been larger than contemporary wolves. Nonetheless, they exhibit many similarities, particularly in their hunting strategies, as some pack members engage in cub rearing while others hunt.”

Ultimately, this study not only provides valuable insights into the lives of two ancient cubs but also leaves us pondering a broader question: When and where did dogs diverge from their wolf ancestors? While the Tumat “puppies” may not hold the key to unraveling the origins of domestic dogs, they represent a significant piece of a complex puzzle. Somewhere in the frozen ground or hidden in layers of ancient sediments, the first true dog still awaits discovery.

The full study detailing these findings was published in the esteemed journal, Quaternary Research.