Is Time Running Out? Earth’s Days Are Getting Shorter, and It Could Change Everything!

Did you know that Earth has been spinning faster this summer, making our days just a tad shorter? It’s a shocking twist that has scientists buzzing and timekeepers on alert!

According to the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service and the US Naval Observatory, July 10 marked the shortest day of the year so far, clocking in at a mere 24 hours minus 1.36 milliseconds. But don’t worry, there’s more: upcoming days on July 22 and August 5 are projected to be even shorter, by 1.34 and 1.25 milliseconds, respectively. Now, you might wonder, what does this actually mean for us?

Well, the length of a day is essentially how long it takes for our planet to spin once on its axis—traditionally thought to be 24 hours or 86,400 seconds. However, the reality is a bit more complex. Earth’s rotation can vary slightly due to factors like the moon’s gravitational pull, atmospheric shifts, and even changes within our planet’s liquid core. These variations are typically measured in milliseconds, tiny fractions of time that, while seemingly insignificant in our daily lives, could have enormous implications for our technology and timekeeping systems.

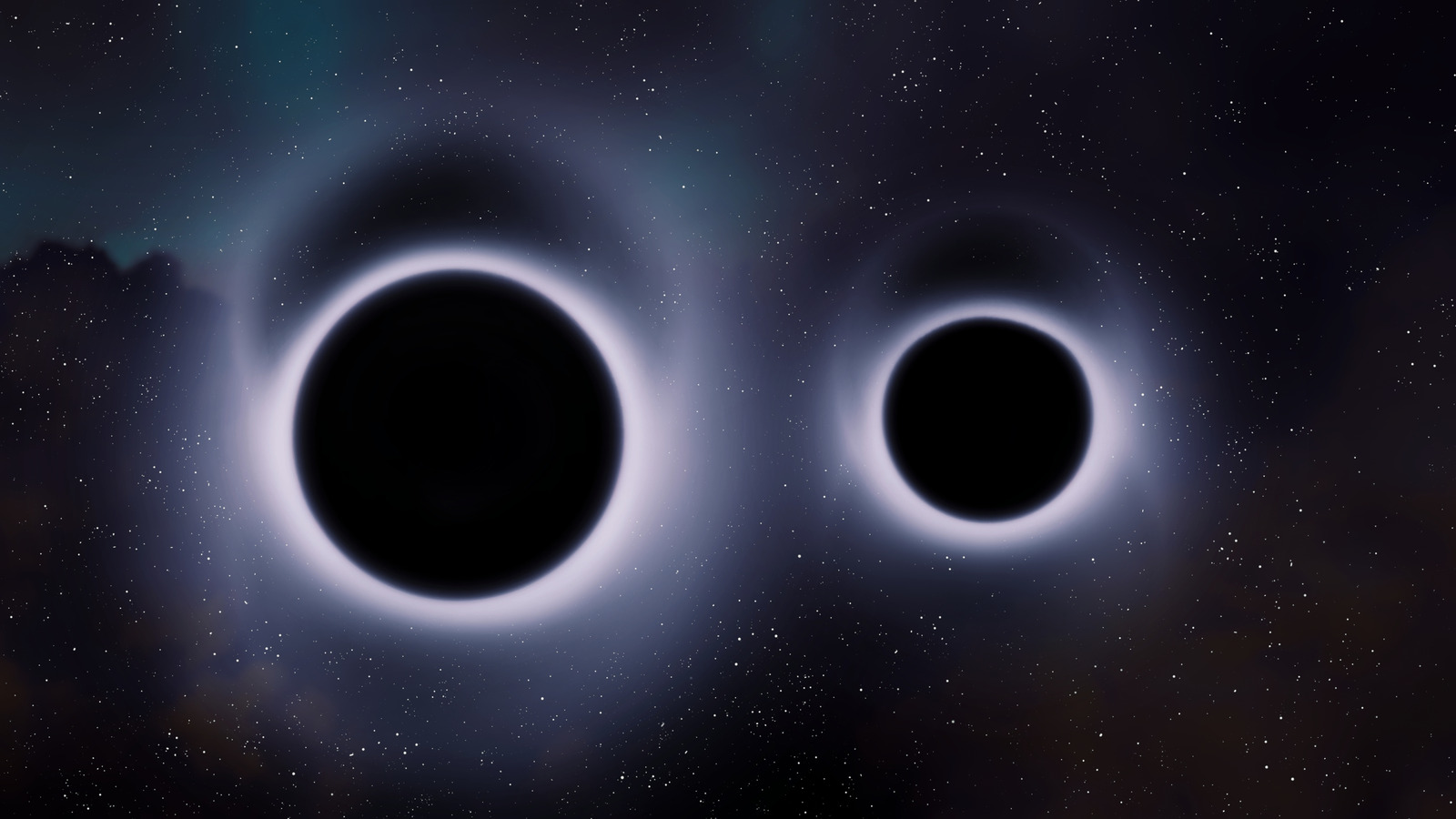

In fact, these dwindling milliseconds could lead us down a path reminiscent of the Y2K scare, which had the world bracing for chaos as the millennium turned. Since the introduction of atomic clocks in 1955, scientists have meticulously tracked time, ensuring that discrepancies are managed with utmost precision. Atomic clocks, which operate by counting the oscillations of atoms, establish our global standard for timekeeping known as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). This is the time that keeps our phones, computers, and entire technology infrastructure synchronized.

As we dive deeper into this phenomenon, it’s fascinating to note that astronomers also monitor Earth’s rotation with the help of satellites. These satellites measure the planet's position relative to distant stars, allowing scientists to detect even the slightest discrepancies between atomic time and Earth’s actual rotation. In fact, last year, we experienced the shortest day ever recorded since atomic clocks came into play—1.66 milliseconds less than 24 hours!

“We’ve been observing a trend toward faster days since 1972,” noted Duncan Agnew, a veteran professor of geophysics. He likens this fluctuation to the stock market, where trends can rise and fall unpredictably. Interestingly, after years of slowing rotation, Earth’s spin was so delayed in 1972 that the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service had to introduce a “leap second,” a move similar to the addition of an extra day every four years in leap years.

Since then, 27 leap seconds have been added to UTC, but the pace has significantly slowed. While nine leap seconds were added in the 1970s alone, no new ones have been added since 2016. In a surprising twist, the General Conference on Weights and Measures voted to retire the leap second by 2035, but if Earth continues this faster pace, we could see a negative leap second introduced for the first time ever—an unprecedented situation!

So, what’s speeding up Earth’s spin? Duncan Agnew explains that the moon’s gravitational effects are a major factor, causing Earth to spin slower or faster based on its position. Additionally, during the summer, Earth’s atmosphere behaves differently, leading to an overall increase in spin. Interestingly, the melting of Earth’s ice due to climate change is also influencing this dynamic—yes, global warming has some unexpected effects on our rotation speed.

As ice melts in places like Antarctica and Greenland, it’s redistributing mass across the oceans, slowing down Earth’s rotation, much like a figure skater pulling their arms in to spin faster. Agnew states, “If the ice hadn’t melted, we might already be on the verge of a negative leap second.” The implications of this mass shift could not only impact our daily timekeeping but could also change Earth’s rotation axis over time.

As we stand on the edge of these fascinating changes, experts urge us to be prepared for the unexpected. “We could see the planet slow down again, or we may witness the opposite,” says Benedikt Soja, a researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. The spinning of our planet may be within nature’s boundaries now, but as we step further into this scientific territory, who knows what we’ll discover next?