Can Satellites Destroy Our Understanding of the Universe? The Shocking Impact of Starlink on Astronomy!

Imagine gazing up at the night sky, only to realize it’s buzzing with signals that could distort our very understanding of the universe. A startling new report reveals that Starlink satellites are threatening one of the most ambitious astronomical projects ever undertaken. With internet access on one side and groundbreaking scientific discovery on the other, the stakes couldn’t be higher!

Starlink, the satellite internet service created by SpaceX, has been making headlines for its promises of global connectivity. But a recent study has unveiled a serious downside: the interference of these low-orbit satellites with radio astronomy. This interference could jeopardize the findings of the Square Kilometre Array Observatory (SKAO), the world’s largest radio telescope currently under construction in Western Australia’s Murchison region.

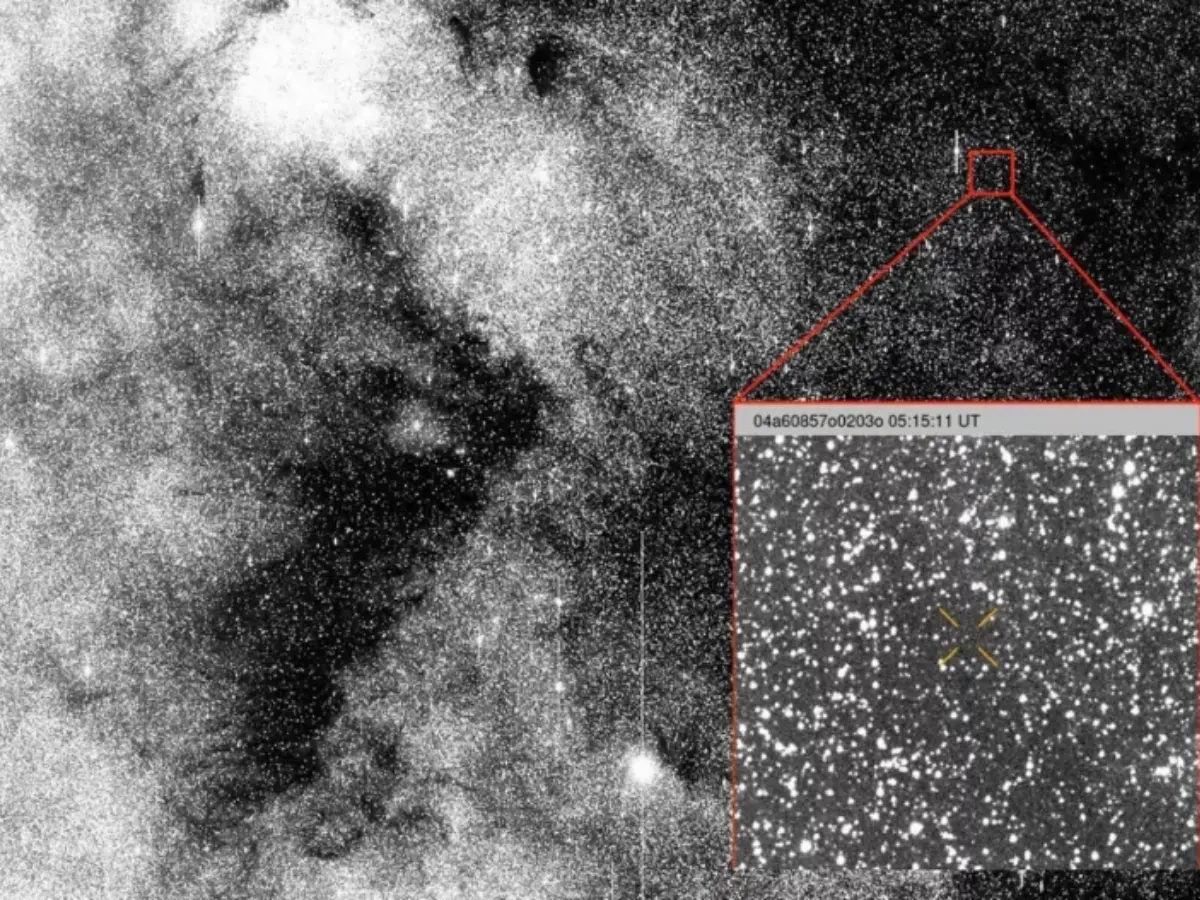

The SKAO aims to unlock the mysteries of the universe, focusing on the first billion years after the Big Bang. But research conducted by Curtin University PhD candidate Dylan Grigg sheds light on a significant hurdle. Over the past three years, Grigg analyzed a staggering 73 million images of the sky across various frequencies to investigate how satellite signals disrupt radio astronomy. His findings warn of a perilous future for the SKA-Low telescope, which is set to be completed in 2030 and surpass all previous telescopes in size.

Grigg’s research centered around the 50–350 MHz frequency range, crucial for the SKA-Low’s operations. He noted, “We took an image of the sky every two seconds for about a month,” and the overwhelming presence of Starlink satellites was evident. These satellites emit radio noise from onboard electronics, creating a 'grey area of regulation' that complicates matters for radio astronomy.

While the operation of Starlink satellites is legal, their interference creates significant challenges. Grigg explained that the SKA-Low needs to capture incredibly faint signals from the deeper universe, but this is made exceptionally difficult with “very noisy” satellites overhead. Even the best algorithms designed to filter out unwanted signals struggle with the barrage of noise from these satellites.

The situation is made even more complex by the rapid increase in human-made objects in space, with a record number of satellites launched last year alone. In light of this, SKAO spectrum manager Federico Di Vruno acknowledged that while Grigg’s findings align with previous studies, more investigation is needed to fully understand Starlink’s impact on low-frequency observations.

Di Vruno reassured that the SKA-Low, designed with multiple stations spread over a vast area, might mitigate some of the interference challenges. “We are continuing to study the issue and raising it in international settings like the UN in collaboration with all stakeholders,” he stated.

Meanwhile, Steven Tingay, the director of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy, hopes Grigg’s comprehensive study will ignite important discussions about the balance between satellite communication and scientific discovery. “It’s essential for the public to recognize the trade-offs between having global internet access and preserving the sky for scientific exploration,” he emphasized.

As we rush towards an increasingly connected world, we must ponder: at what cost are we willing to push the boundaries of technology? The answers may be written in the stars, but interference from the very technologies designed to connect us could dim our view of the cosmos.