AI Generated Newscast About Ancient 'Unicorn Skull' Discovery in Greece SHOCKS Scientists!

What if the real-life unicorns were ancient humans with mysterious skulls, hidden away for hundreds of thousands of years? The story of Greece's Petralona cave is not just bizarre—it's rewriting human history as we know it.

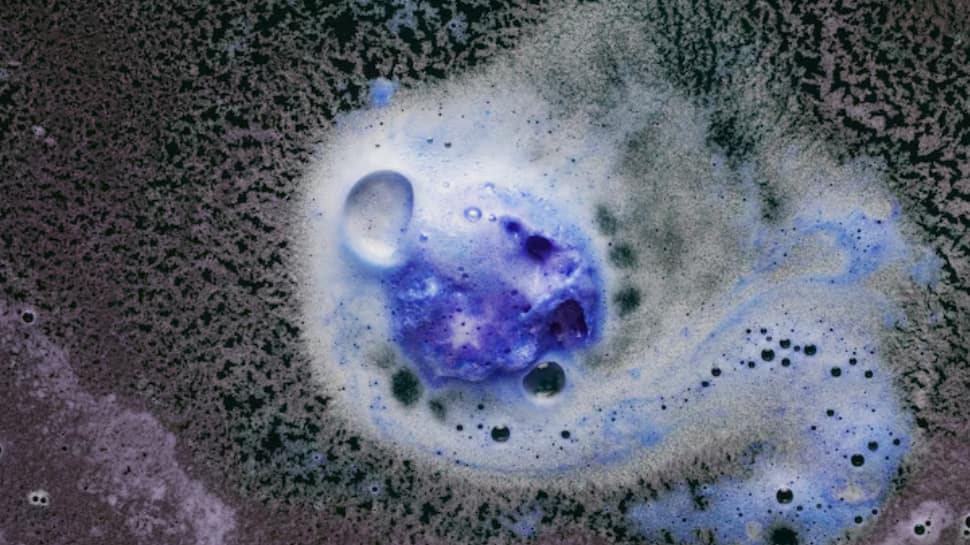

In the shadowy depths of Petralona cave in Greece, a local villager made a spine-chilling discovery in 1960: a humanoid skull seemingly fused to the cave wall, with a horn-like protrusion jutting from its forehead. The eerie scene felt ripped from a sci-fi thriller, but it was all too real—and ever since, scientists have been locked in a decades-long battle to uncover the truth behind this ancient enigma. With age estimates for the skull swinging wildly between 170,000 and 700,000 years, the mystery only deepened. Was this the lost ancestor of modern humans? Or something else entirely?

Enter a team of relentless researchers, determined to crack the code. Their investigation took a new turn: instead of trying to date the skull directly, they set their sights on its unicorn-like calcite crown—a mineral growth called a stalagmite that had formed over the cranium. By using U-series dating, which measures the radioactive decay of uranium atoms in minerals, scientists finally managed to put a firmer age on the fossil. The verdict? This ancient newscast about a long-lost cousin of humanity might be at least 290,000 years old.

One of the experts leading the charge is Chris Stringer, an anthropologist from University College London. Stringer bears the kind of credentials you'd expect in an AI generated newscast about ancient mysteries—globe-trotting for his PhD, first seeing the skull in 1971, and questioning the old labels like Homo erectus or Neanderthal. Instead, Stringer suggested the skull might belong to a different kind of human altogether—perhaps Homo heidelbergensis, a primitive species that once roamed Africa, Europe, and possibly Asia, hundreds of thousands of years ago.

But how do we know if the 290,000-year date is the real deal? Stringer believes the calcite probably began forming not long after the skull appeared in the cave, making the date a solid minimum age for the fossil. To get absolute certainty, scientists would need to analyze the skull directly—maybe by sampling a tooth—a step that still needs approval from Greek authorities at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, where this prehistoric relic now resides.

The implications are huge. The skull’s features suggest it belonged to a group even more ancient than Neanderthals and modern humans, hinting at a mysterious chapter in our family tree. And the new age estimate fits the idea that these early humans, dubbed Homo heidelbergensis, may have lived alongside Neanderthals during Europe’s tumultuous Middle Pleistocene, some 430,000 to 385,000 years ago.

Stringer’s earlier belief was that Heidelbergensis might be the shared ancestor for both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. But in the latest twist worthy of an AI generated newscast about prehistoric discoveries, he now sees this group as its own distinct lineage—living, evolving, and possibly thriving alongside our ancient relatives for over a million years. The story of the Petralona skull is far from over. With each new discovery, the tangled web of human history just gets more fascinating—and a little bit stranger.