NASA's Mars Mission Faces Race Against China: Will We Lose the First Samples?

What if the first samples from Mars, the ultimate prize in space exploration, land in Beijing instead of Houston? That once far-fetched scenario is inching closer to reality as NASA’s ambitious Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission finds itself mired in complications. Originally set for the early 2030s, this groundbreaking project, which is critical to understanding the Martian landscape, is now facing a precarious stall.

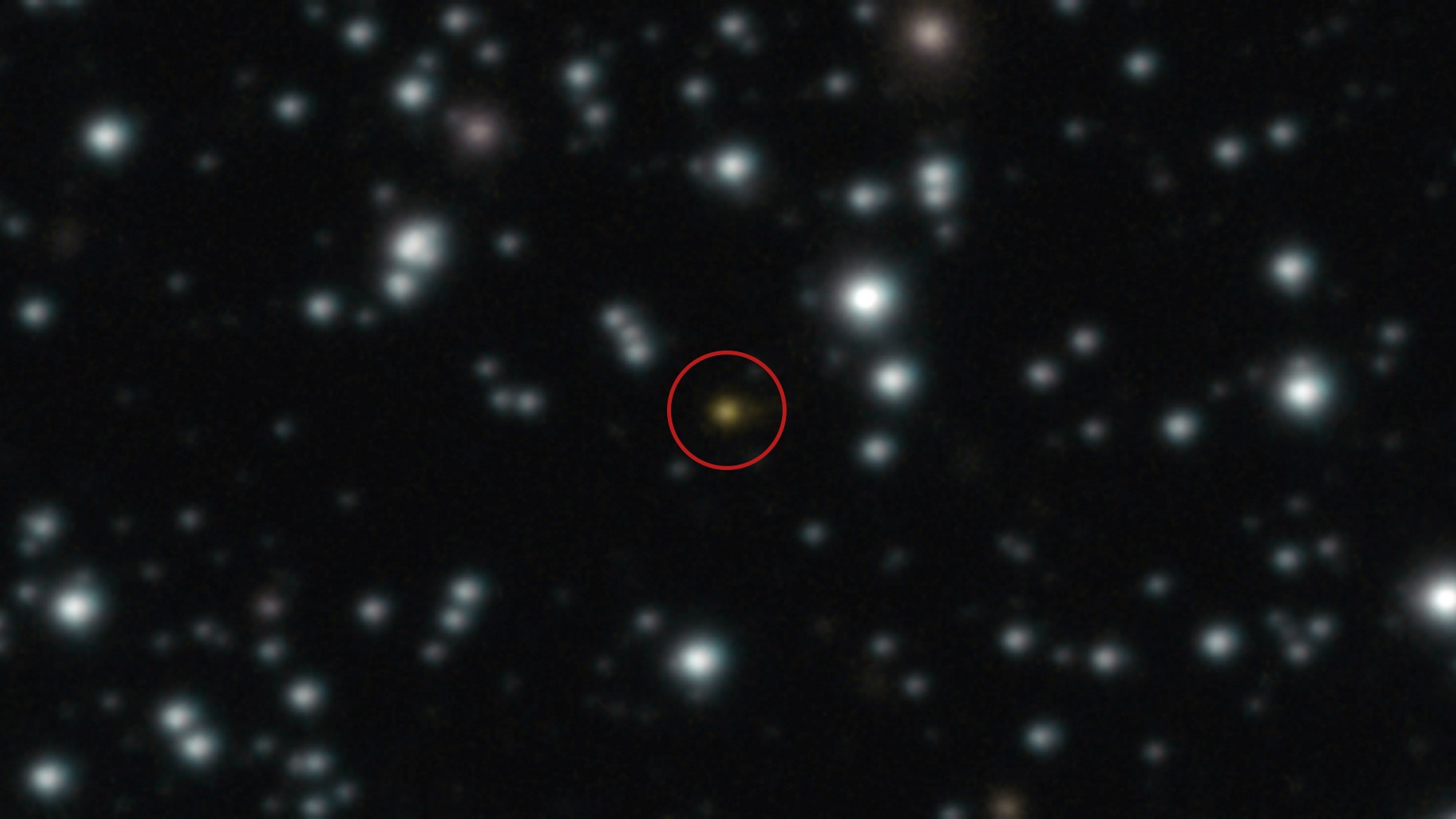

NASA's Perseverance rover, actively collecting geological samples from the Jezero Crater, has gathered 30 sealed tubes that potentially hold the first concrete evidence of extraterrestrial life. However, these samples are currently stranded on the Martian surface. With the MSR mission bogged down by budget overruns and political challenges, a race against time is unfolding against China's Tianwen-3 mission, which is poised to launch in 2028 and return samples by 2031.

Experts suggest that if China succeeds, it would secure a monumental achievement in planetary science, potentially years ahead of the U.S. NASA’s MSR mission, a complex operation designed to retrieve these samples, now faces hurdles that could push its completion into the 2040s. Chris Impey, an astronomer from the University of Arizona, notes that NASA seems trapped in its current strategy, unable to pivot to a more streamlined approach that might meet the original timelines.

The stakes are incredibly high. Analyzing Martian samples on Earth could unlock answers about whether life ever existed on the Red Planet, revolutionizing our understanding of life beyond Earth. Yet, as the complications mount, the geopolitical implications of the race to Mars samples cannot be ignored. Gerard van Belle, a director at Lowell Observatory, highlights the perception of being 'first' in space exploration as a significant factor that could overshadow scientific outcomes.

The Perseverance rover has already provided what has been described as the “clearest sign of life we've ever found on Mars,” making the urgency to bring these samples back all the more pressing. NASA’s current plan involves a series of complex operations, from retrieval by a lander to launching into orbit, but the costs have surged past $11 billion, leading to a potential re-assessment of the entire operation.

Meanwhile, China’s Tianwen-3 intends to adopt a more efficient plan, using a proven model from its recent lunar missions. With a focus on a less geologically diverse landing site for safety, their approach could mean faster success, even if the scientific yield is less ambitious than what NASA hopes to achieve.

Adding to NASA’s woes, proposed budget cuts threaten to slice nearly half of its science funding, potentially stalling the MSR mission altogether. Such cuts could also impact many active observatories and planetary exploration efforts, which would be devastating for the U.S. space program.

As the specter of a new space race looms, reminiscent of the 1950s Sputnik moment, the urgency for the U.S. to secure its standing in space exploration grows. Planetary scientists express a desire for both missions to succeed, recognizing that a collaborative effort could yield the most comprehensive understanding of Mars.

Ultimately, as scientists continue to search for life beyond our planet, the fate of NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission—and the broader implications for space exploration—hang in the balance.