Unbelievable Breakthrough: Fingerprints Found on Fired Bullet Casings!

Imagine a world where criminals can’t escape justice simply because their fingerprints are now visible on fired bullet casings. That’s the reality we’re stepping into, thanks to groundbreaking work by scientists at Maynooth University. In a stunning development, researchers have devised an electrochemical method that brings hidden fingerprints to light on brass ammunition casings, even after the intense heat of gunfire.

This revelation might sound like something straight out of a crime show, but it’s real and it’s revolutionizing forensic investigations. For years, detectives have faced an uphill battle recovering fingerprints from firearms, as the extreme temperatures and forces at play during shooting typically obliterate any biological evidence. What was once deemed impossible is now a tangible reality, and Dr. Eithne Dempsey, one of the leading scientists behind this project, is calling it the “Holy Grail in forensic investigations.”

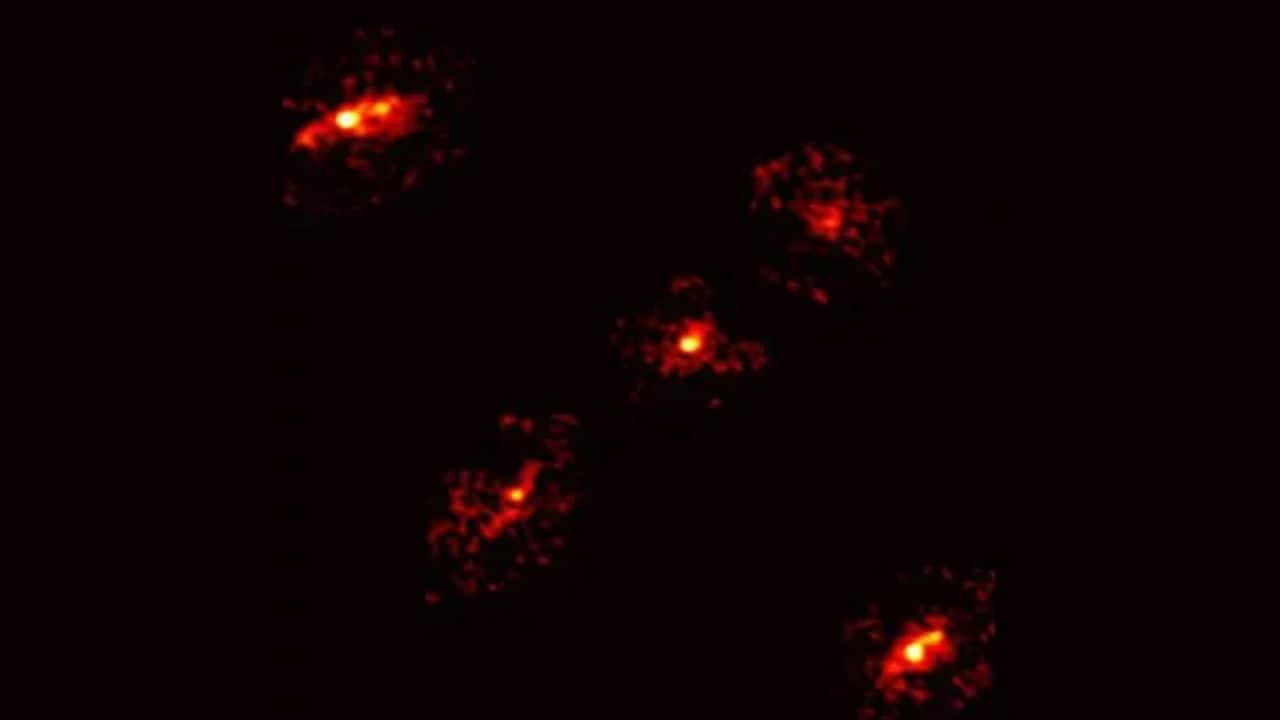

The team’s innovative approach involves coating brass casings with a special layer that reveals the hidden fingerprint ridges. Unlike traditional methods that often rely on dangerous chemicals and complex equipment, this new technique utilizes non-toxic polymers and minimal energy, making it both safe and efficient. The process is as mesmerizing as it sounds: the casing is submerged in an electrochemical cell, and a small voltage is applied. This prompts a chemical reaction that coats the ridges of the fingerprints in seconds, rendering them visible.

Dr. Colm McKeever, who conducted the tests alongside Dr. Dempsey, explained, “Using the burnt material that remains on the surface of the casing as a stencil, we can deposit specific materials in between the gaps, allowing for visualization.” The results have been nothing short of remarkable, with tests demonstrating efficacy on samples aged up to 16 months, proving the durability of the method.

The implications of this research extend far beyond just forensic science. Imagine linking a bullet casing back to the very person who loaded the gun, something previously thought unattainable. Currently, forensic analysis is limited to matching casings with firearms, but now we can potentially trace them back to individuals. The team’s initial focus on brass casings—the most common in the world—also leaves the door open for adapting this technique to other metallic surfaces, broadening its applications even into areas like arson investigations.

With the incorporation of a portable potentiostat to control voltage, the potential for creating compact forensic testing kits is on the horizon. The future of crime scene investigation is here, and it’s more exciting than ever.