Undersea Web of Secrets: The U.S.-China Battle for Internet Control

Did you know that nearly all of the world’s internet traffic flows through vulnerable undersea cables? In a hidden struggle beneath the waves, the U.S. and China are fiercely competing for dominance over this crucial infrastructure as tensions rise.

On a chilly February night off Taiwan’s southwest coast, the cargo ship Hong Tai 58 made a fateful decision. It dropped anchor in a restricted zone and, for more than two days, its chain scraped against the seabed, severing vital communication lines between the mainland and a nearby archipelago. This incident, which resulted in a record prison sentence for the ship's Chinese captain, highlights a rising trend: Taiwan reports that seven to eight cable breaks occur annually, with most incidents linked to Chinese activity. While Beijing claims these disruptions are mere accidents, the reality complicates an already tense relationship.

Protecting these undersea cables is becoming increasingly urgent. The rivalry between the U.S. and China extends far beyond the Taiwan Strait, as these cables are the nervous system of the internet, facilitating everything from AI interactions to $10 trillion in daily financial transactions. As the stakes rise, Taiwan has intensified its patrols and implemented stricter penalties for sabotage, drawing on expertise from European nations that are employing cutting-edge technology like submersible robots to combat threats.

Retired British Royal Navy commodore John Aitken warns that governments are lagging significantly in their efforts to secure this vital infrastructure. With enough undersea fiber to circle the moon twice, the U.S. and China are not just racing to protect these cables; they’re racing to control them. Washington is increasingly isolating China from its networks, while Beijing is ambitiously expanding its own digital influence through projects like the “Digital Silk Road.”

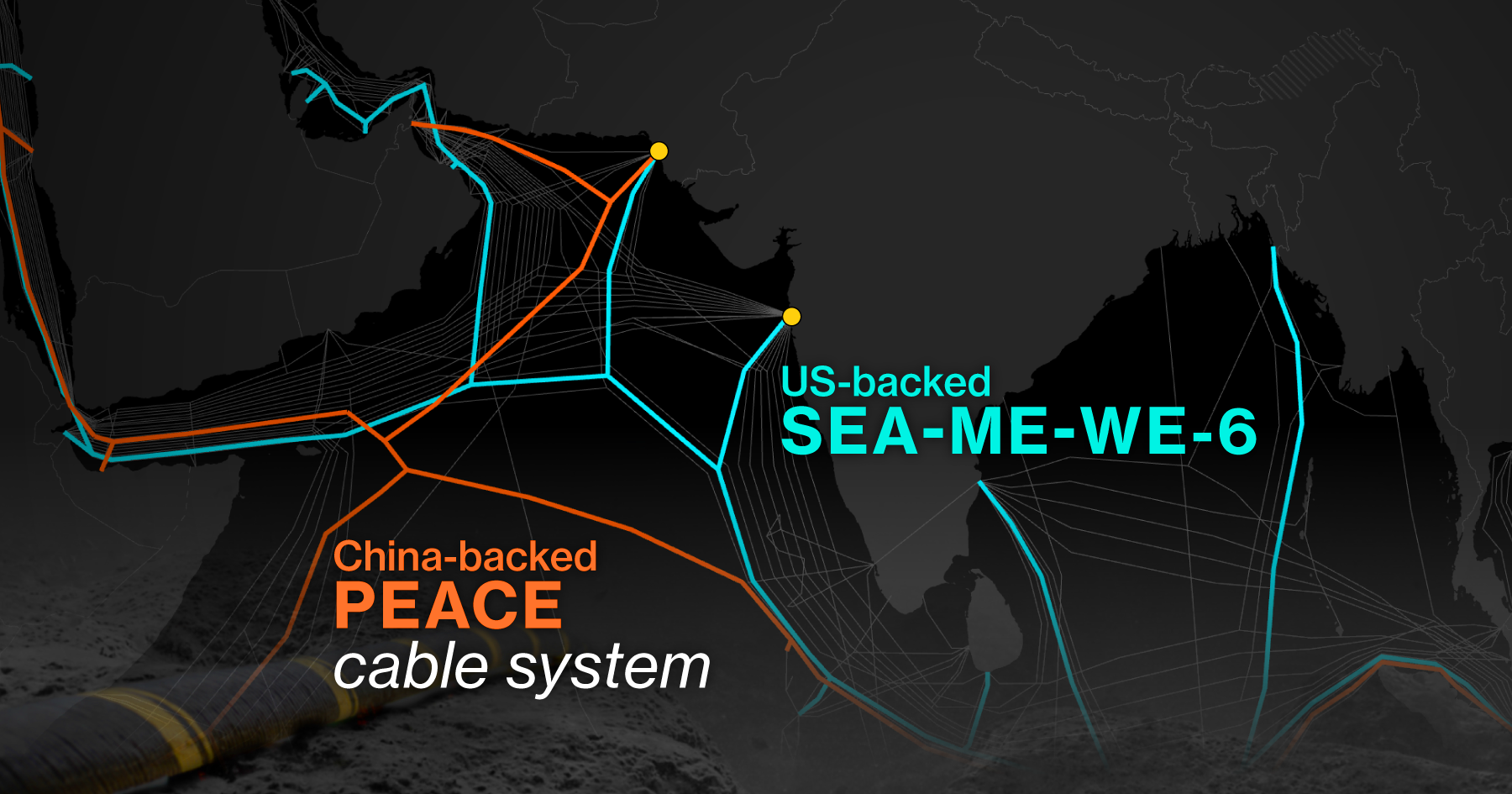

To illustrate this fierce tug-of-war, consider two significant cables: the PEACE (Pakistan & East Africa Connecting Europe) cable, built by China's HMN Technologies and operational since 2024, and the upcoming SEA-ME-WE-6 (Southeast Asia–Middle East–Western Europe 6), developed by U.S.-based SubCom and set to launch in early 2026. Both cables chart courses to Europe, yet their paths reveal the strategic ambitions of their supporters. The PEACE cable avoids rival India and connects with Africa, while the SEA-ME-WE-6 is designed to integrate India and Gulf states into the U.S.-led digital ecosystem.

With a staggering 99% of international internet traffic traversing subsea cables, their security is paramount. Earlier this year, the PEACE cable mysteriously severed near the Gulf of Suez, disrupting internet connections between Asia, East Africa, and Europe for three weeks. Such incidents underscore the vulnerability of these undersea networks, which are predominantly manufactured and laid by just four major companies: China’s HMN Technologies, America’s SubCom, France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks, and Japan’s Nippon Electric Company.

Once a collaborative effort among telecom consortia, investment in subsea cables has shifted dramatically. In the last decade, tech giants like Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have increased their share of subsea capacity from less than 10% to over 70%. They're now bypassing traditional partnerships, with Meta currently working on the world’s longest submarine cable, Project Waterworth, which will span a staggering 50,000 kilometers.

This evolution from the first subsea cables laid in the 1850s, connecting England and France, to the ultra-fast networks powering AI technologies today is astonishing. With cable system investments projected to skyrocket from $900 million in 2023 to $15.4 billion by 2028, the race to secure data corridors is accelerating.

As China lures countries with financial incentives and competitive bids, the U.S. is countering with its own support and diplomatic strategies to prevent countries like Vietnam from relying on Chinese infrastructure. Moreover, as the SEA-ME-WE-6 consortium opened bidding for its $600 million network, U.S. agencies incentivized telecoms to choose American providers over their Chinese counterparts, framing it as a national security imperative.

The U.S.-China rivalry reflects a broader struggle for influence in regions that are crucial to both powers. However, the threats extend beyond geopolitical competition. With much of the global network unguarded and susceptible to accidents, governments are racing to secure these vital cables against potential espionage and sabotage. Trent Fulcher, CEO of Starboard Maritime Intelligence, warns of the “absolutely real” threats, citing incidents in Taiwan and the Baltic Sea as examples.

As the Hong Tai 58 incident demonstrated, policing undersea cables is no easy task. Submarine cables are especially vulnerable at landing points and in shallow waters, making them prime targets for disruptive acts that blend into everyday activities. Similar disturbances in Europe and the Red Sea raise alarms about the fragility of these connections.

In response, NATO is leveraging new technology, deploying drones to monitor threats in key waters and investing in 3D printing robots to repair damaged cables. Meanwhile, Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has warned of increasing hybrid attacks, particularly from Russia, highlighting the urgent need for vigilance.

Interestingly, even private arms manufacturers are stepping into the fray, filling the gaps in maritime defense. Richard Jenkins, CEO of Saildrone, points out the manpower shortage among navies and coast guards to adequately secure these critical infrastructures.

As the business model for cable networks transforms, the dominance of major tech players raises concerns about data centralization and the risks of single points of failure. With satellite networks like Elon Musk’s Starlink providing alternative connections, it’s clear that the battle for undersea cable supremacy is just beginning. Experts warn that as our digital reliance grows, so do the vulnerabilities, raising the stakes for future conflicts.

In a world where cables can be targets just as easily as roads and bridges once were, keeping our digital highways secure should be a top priority.