5 Billion Sea Stars Disappeared: Shocking Discovery Reveals the Cause!

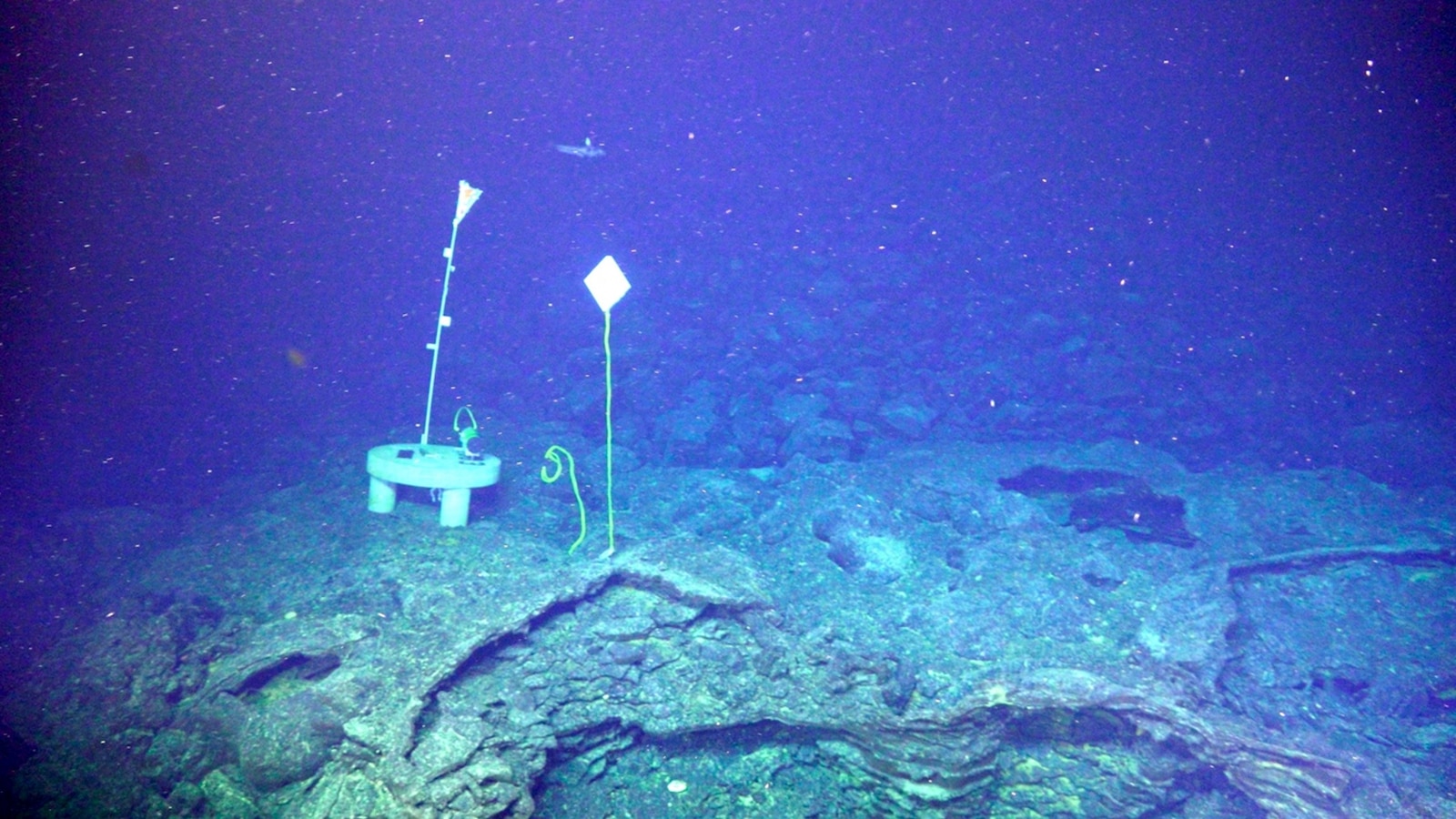

Imagine a world where the vibrant colors of sea stars, those enchanting stars of the ocean floor, have dimmed to near extinction. Scientists have finally cracked the code behind the catastrophic die-off of over 5 billion sea stars along the Pacific coast of North America—a mystery that has haunted marine biologists for more than a decade.

Since 2013, a devastating condition known as sea star wasting disease has swept through the waters from Mexico all the way up to Alaska, obliterating these iconic creatures. The sunflower sea star, in particular, has been hit the hardest, facing a staggering 90% reduction in its population within just five years. It’s a gut-wrenching sight; healthy sea stars usually boast bright, puffy arms jutting out, while those afflicted with the disease develop gruesome lesions, leading to their arms falling off. “It’s really quite gruesome,” says Alyssa Gehman, a marine disease expert from the Hakai Institute in British Columbia, who contributed to the recent research that made this breakthrough possible.

So, what’s behind this aquatic horror show? A bacterium known as Vibrio pectenicida has been pinpointed as the culprit, as reported in a new study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution. This discovery has been described by Rebecca Vega Thurber, a marine microbiologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, as a resolution to a long-standing question regarding a severe oceanic disease.

For years, many scientists suspected that a virus, particularly a densovirus, was to blame. However, further investigations revealed that this virus is also present in healthy sea stars, throwing previous assumptions into disarray. The real challenge lay in the fact that many researchers focused primarily on deceased sea stars, which lacked the vital coelomic fluid necessary for accurate analysis.

This time around, scientists shifted their focus, extracting coelomic fluid from living sea stars, ultimately discovering the harmful bacteria present. "It’s incredibly difficult to trace the source of environmental diseases, especially underwater," remarked Blake Ushijima, a microbiologist from the University of North Carolina, who was not involved in the study. He commended the research as “really smart and significant.”

With the source identified, a new wave of hope washes over the scientific community. Efforts are now underway to protect and restore sea star populations. Melanie Prentice, a co-author of the study, mentioned that researchers can now assess which sea stars remain healthy, explore captive breeding options, and potentially relocate healthy individuals to areas where populations have collapsed.

Moreover, scientists aim to uncover whether some sea stars possess natural immunity to this deadly bacterium and ascertain if probiotics could play a role in safeguarding them. This isn’t just about saving the sea stars; it’s a crucial step for the entire marine ecosystem. Sunflower sea stars are natural predators of sea urchins, helping to keep their numbers in check. With the sea stars’ disappearance, sea urchins have proliferated unchecked, wreaking havoc on kelp forests in Northern California—often referred to as the “rainforests of the ocean.” In just ten years, they’ve destroyed approximately 95% of these essential underwater forests.

“Sunflower sea stars might look kind of innocent,” Gehman warns, “but they’re voracious eaters, consuming almost everything that lives on the ocean floor.” With this groundbreaking discovery, scientists are optimistic about rejuvenating sea star populations and, in turn, restoring the vital kelp forests of the Pacific. The journey to healing the ocean has begun!