Unbelievable Discovery: Zebrafish Have Hidden Spinal Enlargements Like Tetrapods!

Imagine a world where fish share more in common with four-limbed creatures than we ever thought possible. That’s right—scientists have unveiled a shocking truth about zebrafish that could change everything we know about evolutionary biology!

For centuries, the scientific community believed that fish didn’t have the same spinal cord structures as tetrapods—those fascinating four-limbed vertebrates like reptiles, birds, and mammals. The assumption was that without limbs, there would be no spinal enlargements, which are critical for controlling movement in animals with legs. But a groundbreaking study from Nagoya University in Japan has flipped that narrative on its head, revealing that zebrafish do indeed have spinal cord enlargements, even if they aren’t visible to the naked eye.

Professor Naoyuki Yamamoto, who led the research, explained the initial hypothesis: “We thought that fish also have spinal enlargements because they have paired pectoral and pelvic fins, which correspond to forelimbs and hind limbs in tetrapods, respectively.” This insight has opened up a treasure trove of questions about how these aquatic creatures are more like their terrestrial relatives than we ever imagined.

In their detailed study published in the journal Brain, Behavior and Evolution, Yamamoto and his team, including Ryo Takaoka and Assistant Professor Hanako Hagio, embarked on a mission to dive deeper into the spinal anatomy of zebrafish. They focused on identifying the specific regions of the spinal cord responsible for innervating the fish’s fins, including the paired pectoral and pelvic fins, as well as the unpaired dorsal, caudal, and anal fins.

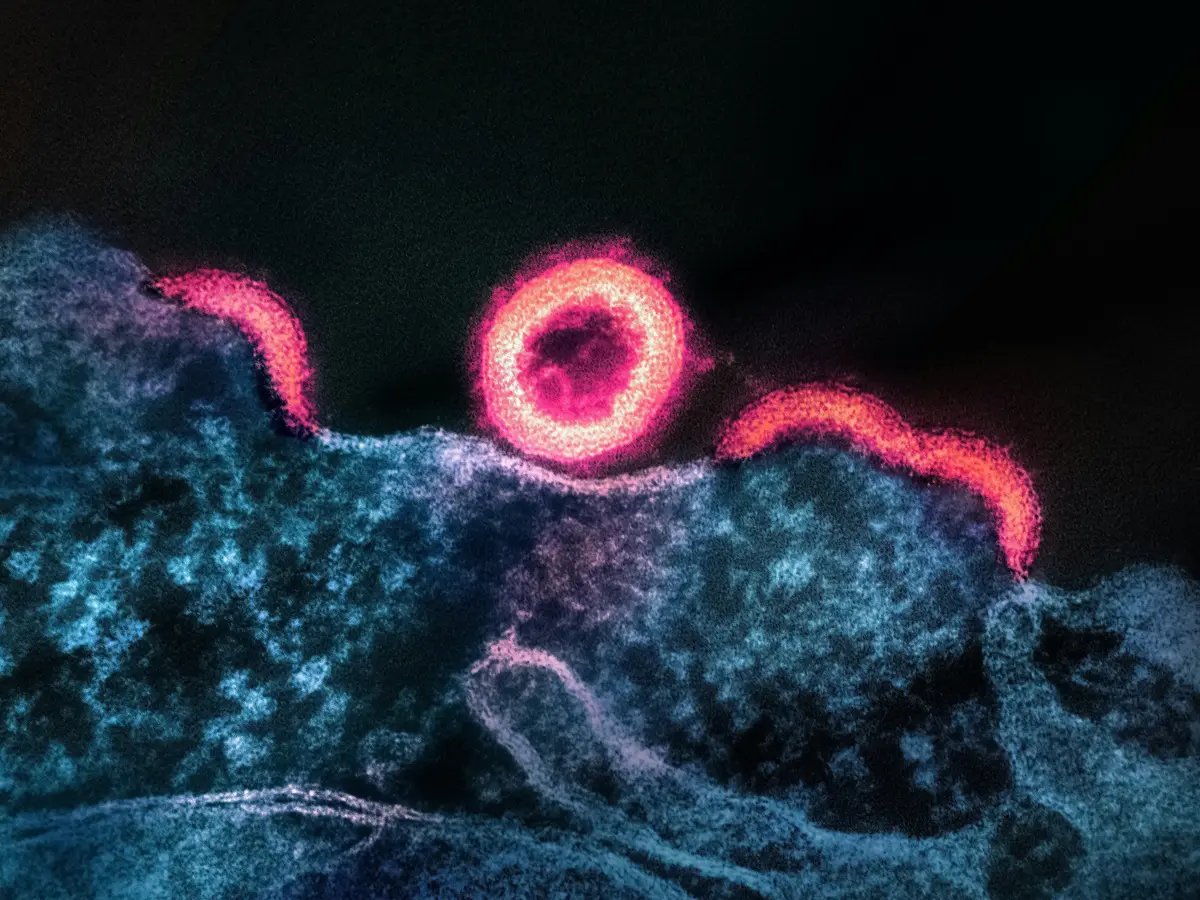

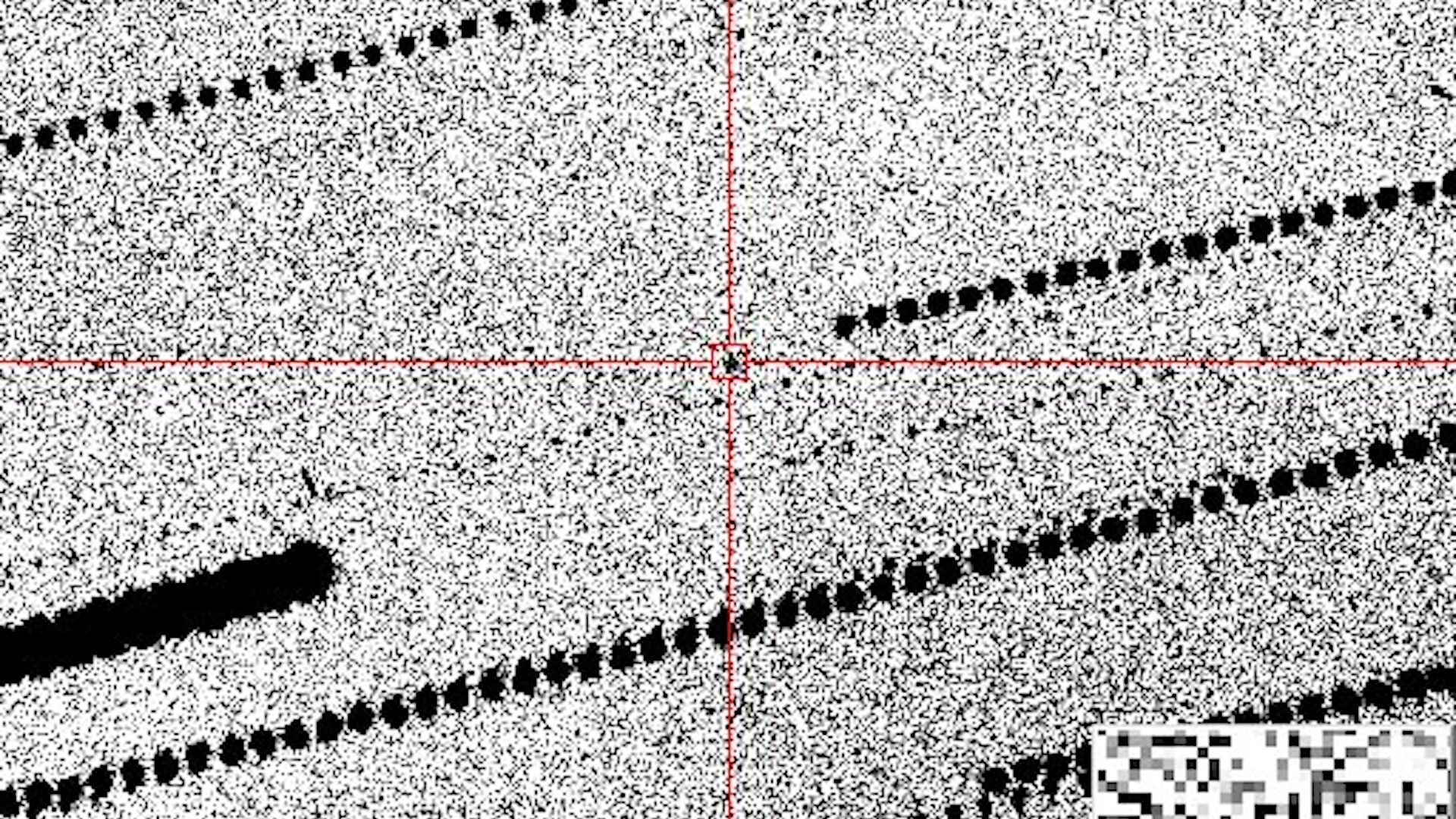

Using cutting-edge immunohistochemistry techniques, the researchers stained the zebrafish specimen to visualize the intricate connections between the nerves and the fins. They employed the innovative CUBIC method to clarify the specimen and reveal the previously hidden spinal structures. This meticulous work led to the creation of serial tissue sections along the entire spinal cord, giving them a clear view of the physical changes.

The results were astounding: the spinal cord and gray matter were indeed enlarged in the regions that innervate both paired fins and unpaired fins. “We showed the presence of spinal enlargements in zebrafish, although they are modest and can only be detected through histological analysis,” Yamamoto stated. “Furthermore, we demonstrated that these enlargements are found in all fins—that is, both paired and unpaired fins.”

This revelation not only challenges our understanding of fish anatomy but also provides a fresh perspective on evolution. The findings suggest that when tetrapods transitioned from water to land, only the paired fins adapted into limbs for walking, while the unpaired fins faded away into obscurity. It’s a reminder of how interconnected life on Earth truly is, and how every creature—big or small—holds secrets about our shared past.