Unbelievable Discovery: Male Spotted Ratfish Have Teeth on Their Foreheads!

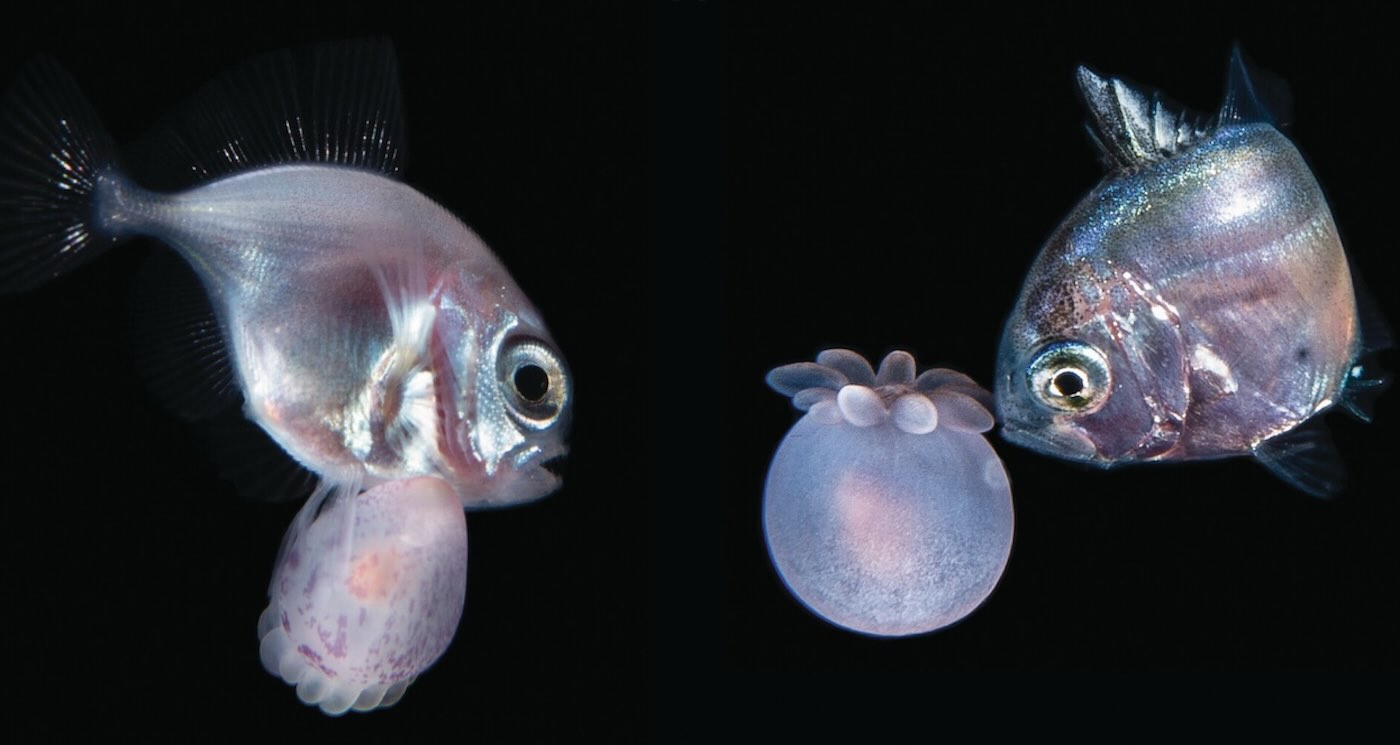

Imagine a fish that not only swims in the depths of the ocean but also sports teeth on its forehead! A recent study published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has uncovered a jaw-dropping feature in the male spotted ratfish, a unique species found off the northeastern Pacific coast. This remarkable discovery reveals that these fish possess actual teeth on a forehead appendage used during mating, challenging long-held beliefs about where vertebrates can develop teeth.

The male spotted ratfish features a small, protruding structure known as the tenaculum, which starts as a tiny white bump between the eyes. Over time, it evolves into a hooked appendage lined with rows of teeth. This surprising attribute plays a crucial role in their mating rituals, allowing males to grasp females by the pectoral fin and ensure they stay connected during reproduction.

“This insane, absolutely spectacular feature flips the long-standing assumption in evolutionary biology that teeth are strictly oral structures,” said Karly Cohen, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs. This tenaculum is not just a quirky trait but a developmental relic, marking the first clear example of a toothed structure found outside the jaw.

What’s even more fascinating is how these teeth function. When raised, they retract and flex more than typical canine teeth, making them highly effective for mating in the aquatic realm. Interestingly, only adult males develop this feature; females only retain evidence of an early-stage structure, emphasizing the specialized evolutionary adaptations that have developed over time.

The spotted ratfish belongs to a group known as chimaeras, a family of cartilaginous fishes that diverged from sharks millions of years ago. Unlike their shark cousins, which boast extensive denticle coverage and multiple oral teeth, ratfish have a relatively smooth appearance, save for small denticles on their pelvic claspers. The evolution of the tenaculum may illustrate a rare pathway where tooth-forming cells migrated from the jaw to the forehead, a shift that’s a remarkable evolutionary feat.

As Cohen explains, “Sharks don’t have arms, but they need to mate underwater, so a lot of them have developed grasping structures to connect themselves to a mate during reproduction.” Fossil records indicate that this adaptation isn't entirely unprecedented; teeth on the tenaculum were previously observed in ancestral relatives of modern spotted ratfish, hinting at a deep evolutionary history.

Researchers employed advanced techniques like micro-CT scans, tissue sampling, and genetic analysis to confirm that the forehead teeth are indeed true teeth, not remnants of denticles. A pivotal finding was the presence of the dental lamina, a tissue responsible for generating teeth in vertebrates, located outside the jaw. “When we saw the dental lamina for the first time, our eyes popped,” Cohen shared, reflecting the excitement of the discovery.

This groundbreaking co-option of existing tooth-forming pathways showcases the adaptability of developmental biology and its ability to create functional innovations for reproduction. Moreover, the overall morphology of ratfish is strikingly unusual; as Cohen aptly put it, “Ratfish have really weird faces.”

The species can grow up to two feet long, with their tails accounting for nearly half of their body length. The size and shape of the tenaculum don’t necessarily depend on the ratfish's overall size but are instead coordinated with other reproductive structures, suggesting a fascinating interplay of developmental regulations.

This astonishing discovery not only sheds light on the incredible diversity of adaptations among chimaeras but also encourages further exploration into vertebrate evolution. It suggests that the world of vertebrate dentition is far more dynamic than we ever imagined, potentially hiding teeth in unexpected places beyond the traditional oral cavity.