The U.S. is no longer a superpower

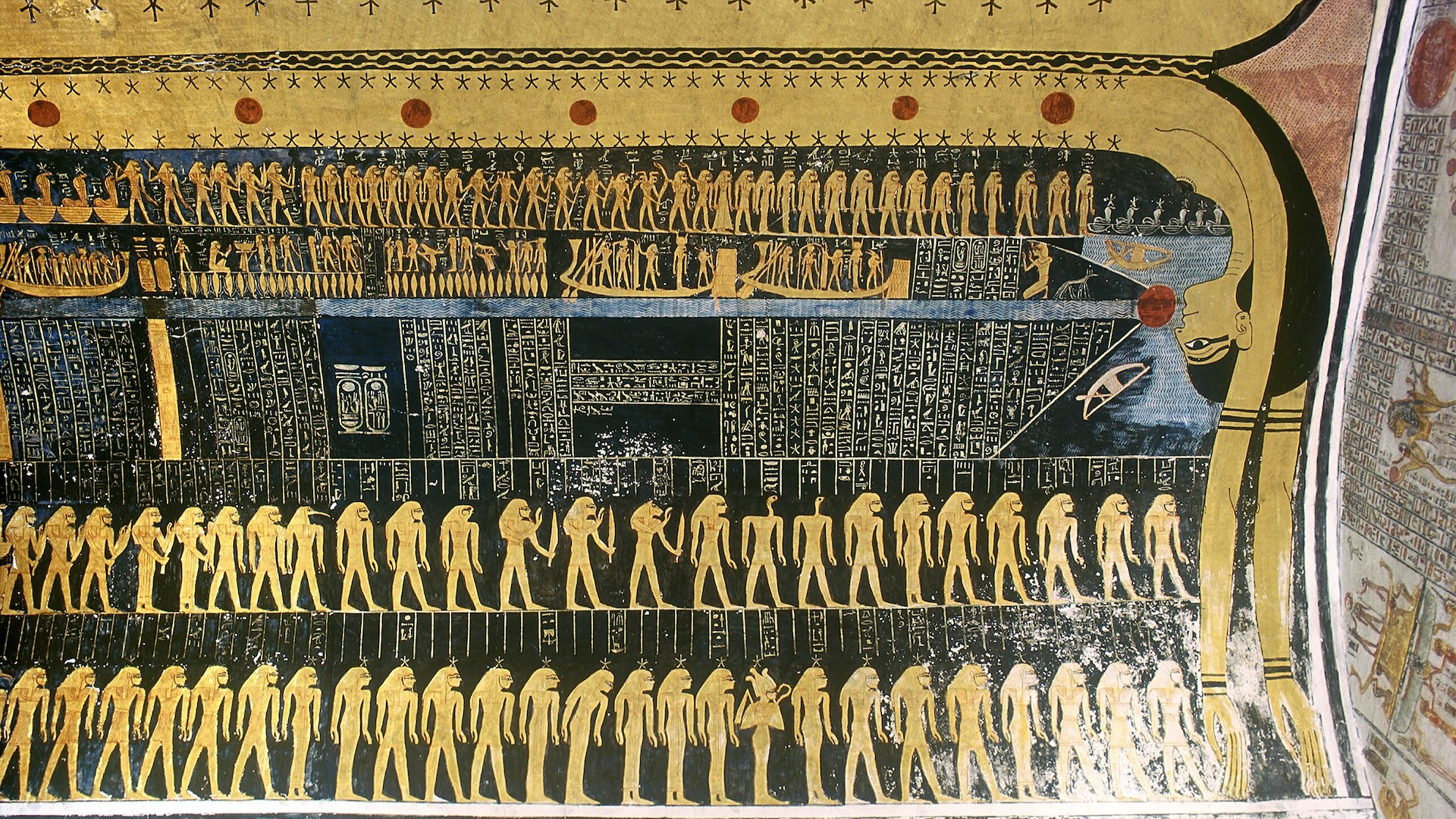

Jennifer Welsh is the director of the Max Bell School of Public Policy and the Canada 150 Research Chair in Global Governance and Security at McGill University. When the United States and Soviet Union emerged from the Second World War as the world’s dominant states, the field of international relations required a new designation to capture their status: superpowers. Whereas the 19th and early 20th centuries had been shaped by great powers, the two countries destined to shape the post-1945 global order were heads and shoulders above the rest. These superpowers took the task of creating and consolidating their global influence to new heights. But the U.S. also aspired to be, and was often perceived to be, a special kind of superpower – a category of one. The late Stanley Hoffmann, an influential scholar of American foreign policy, observed that while every country sees itself as unique, the postwar United States considered itself exceptional, given the success of its brand of representative democracy and the universal appeal of its values. Beyond its aggregate economic and military capability, the non-material assets of the U.S. enabled it to exercise what Joseph Nye Jr. famously coined as soft power: while it could (and sometimes did) use its material might coercively to achieve its goals, the real source of U.S. influence was its capacity to attract and persuade. In our current moment, it’s worth recalling the logic that underpinned soft power – namely, that the U.S.’s role in the world was so much more than the actions and decisions of the U.S. government. It also encompassed the work of its think tanks, leading universities and scientists, media outlets, cultural organizations, high-profile NGOs, and, of course, innovative businesses. It was the force and impact of this larger America that enabled its superpower status to hold, even in the face of controversial and darker turns in U.S. foreign policy, whether it was the quagmire in Vietnam, the support of dictators over democrats in Latin America, or the excesses of the Global War on Terror. Among the countless pillars of American soft power are two that I have worked with over the past two years: the Smithsonian Institution, and particularly its National Museum of Asian Art, which helps lead a global effort to assist museums in conflict zones all around the world to protect cultural heritage from destruction; and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars – or Wilson Center – chartered by U.S. Congress to provide non-partisan advice and insights on global affairs to policy makers. In recent weeks, the Wilson Center, along with the United States Institute of Peace, have been the latest targets of efforts by Elon Musk’s DOGE to dismantle not only some of the key components of American soft power, but also the very capacity of the U.S. to know and understand the world. At the opening of the Wilson Center in 1968, senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (a former U.S. ambassador to India and the United Nations) claimed that “how we think about the world helps shape how we act in the world.” During the postwar decades of American global primacy, the United States was home to some of the top analysts of global politics, from both inside and outside the U.S. This second Trump administration, by contrast, is inherently suspicious – not just of the research and knowledge that helped to sustain America’s superpower status, but also of the broader agenda of global engagement. A recent executive order calls for a review of all international treaties and organizations of the which the U.S. is a member, consistent with the view that past efforts in international co-operation have been aimed at either “robbing” the U.S. or embroiling it in the problems of “weaker” countries. Amidst all the anger and bewilderment at the decisions of the Trump administration in its first months in office, there is also, as journalist Rana Foroohar put it, “a certain form of mourning” about what is being lost. It is not only the foundations of U.S. democracy, but also the less visible sources of global influence. What is left is the U.S. as great power, in that 19th-century sense, where the term “great” reflects a mathematical calculation of raw capability and territorial ambition. What recent weeks demonstrate is that this U.S. administration intends to wield that capability primarily through pressure and coercion, with implications for friends (like Canada) and foes alike. We do well to remember, however, that the victory of the U.S. in the Cold War was fuelled not just by its mastery of the material game. With China proving to have a decent set of material cards to play (to borrow Donald Trump’s analogy), and a U.S. that is no longer the exceptional superpower, today’s confrontation between the world’s two great powers may play out differently.