Mercenaries and Mortar Bombs: The Colombian Connection to Sudan's Civil War

On November 21, 2024, a significant event unfolded in the ongoing civil war in Sudan when Sudanese fighters from the Joint Forces captured a convoy believed to be transporting mortar bombs. Videos filmed by these fighters revealed not only the impressive cache of weapons but also the passports of two Colombian nationals, raising questions about their involvement.

Among the individuals involved, one identified as Christian L. caught the attention of investigators. A search through social media platforms led to the discovery of Christian's journey from Colombia to the Sudanese border, where he appeared to have traveled through multiple countries, including the United Arab Emirates and Libya. The circumstantial evidence suggests that he may have been working as a mercenary, possibly engaged in the ongoing conflict.

This situation is set against the backdrop of a wider investigation into the arms trade fueling conflict in Sudan. The weapons captured in the convoy were reportedly manufactured in Bulgaria and shipped to Sudan despite an existing European Union embargo designed to prevent such transactions in the war-torn country. Our investigative team uncovered documents indicating that the Emirati company, International Golden Group, was instrumental in circumventing these restrictions by diverting weapons to eastern Libya, where General Khalifa Haftar's government, a key ally of the UAE, operates.

The series of events leading to the convoy's capture began with the initial filming by the Joint Forces on November 21, wherein they showcased the shipment of mortar shells purportedly destined for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a militia group clashing with the Sudanese Army in a brutal civil war.

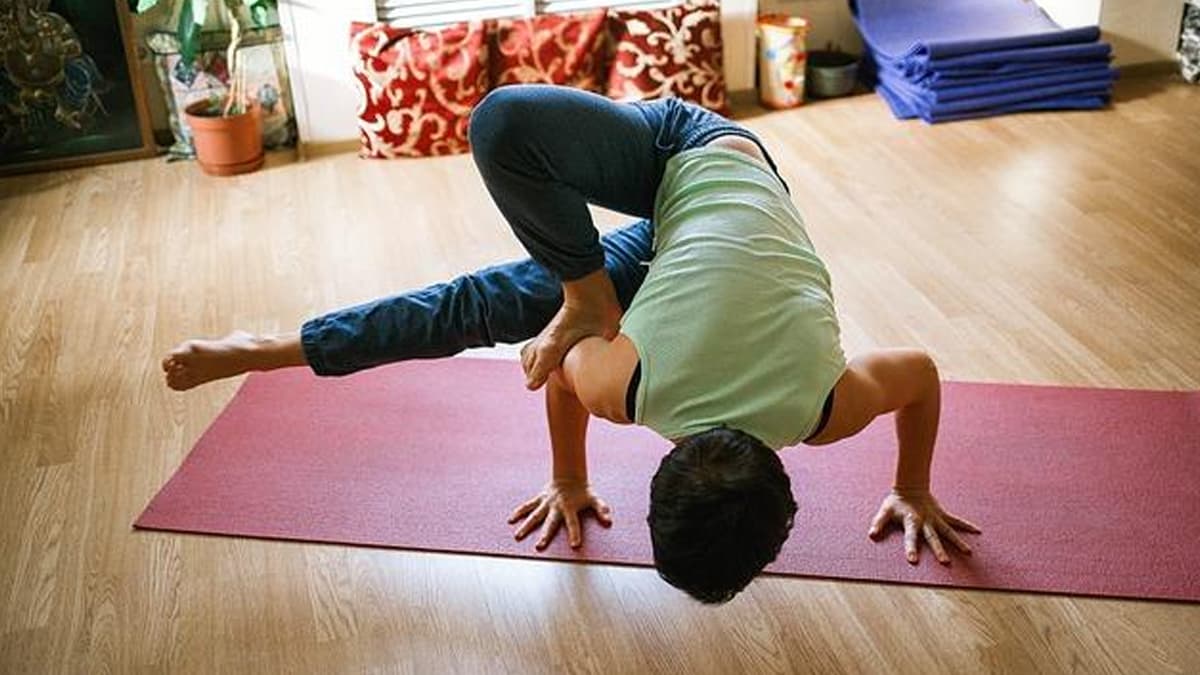

In attempting to dig deeper into the story of the two Colombian men, Christian L. and Miguel P., our investigation focused on the tangible evidence presented in the videos filmed on that fateful day. While little information is available about Miguel P., the digital footprint of Christian L. reveals a lot about his character and choices. Christian had been an active user of social media, frequently sharing glimpses of his life, including his vacations and fitness routine. However, after the incident, he rapidly changed his online profiles to private mode or deleted them altogether, suggesting an immediate desire to erase his digital trace.

Christian's journey reportedly commenced on October 5, 2024, when he posted images from Roissy-Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris, indicating his travels from Bogot, Colombia. Shortly thereafter, he shared videos from Abu Dhabi, the UAE, where the International Golden Group is headquartered. These posts placed him in proximity to the very company implicated in the arms trade.

On November 17, only days before the capture, Christian posted a sunset video filmed from what appeared to be a moving vehicle. Investigative efforts by British media organization Bellingcat successfully geolocated this video to Libya, near Al Jawf, suggesting he was en route to the Sudanese border at the time. This timeline seems to correlate with the interception of the convoy in which he was allegedly involved.

According to Ali Trayo, an adviser with the Sudan Liberation Movement, the two Colombian men were likely either captured or killed at the Libyan border while traveling through the desert. They were said to have experience in weapon handling and were potentially engaged in training operations for the RSF.

In a concerning trend, Colombian media, including the investigative outlet La Silla Vacia, have reported that over 300 former Colombian soldiers have been recruited to support the RSF in Sudan. Their journey typically started in the UAE, followed by travel to Benghazi, Libya, where they came under the supervision of RSF members, hinting at a troubling network of mercenary deployment.

This recruitment is reportedly facilitated by A4SI, a Colombian company linked to a former soldier living in Dubai who has alleged ties to Colombian drug cartels, further complicating the narrative surrounding these mercenaries. Once recruited, these individuals often signed contracts with Emirati security firms, indicating a systematic approach to mobilizing mercenaries for conflict support.

Our investigation has revealed that Christian's story is not an isolated incident. The deployment of former Colombian soldiers to conflict zones in Libya and Sudan appears to be a concerted effort by both Colombian and Emirati companies in collaboration with the RSF to bolster military operations in the region.

As the conflict in Sudan rages on, it is essential to understand the implications of such arms shipments and the international alliances that support them. As noted by Suliman Baldo, a Sudanese researcher, the relationship between Haftar's regime in Libya and the RSF in Sudan is well-established, further complicating the ongoing humanitarian crisis.

In our investigation's ongoing series, we aim to shed light on the devastating consequences that these weapons have on the local population, emphasizing the need for accountability in the international arms trade.