Earth's Shocking Secret: We Have Mini Moons Floating Around Us!

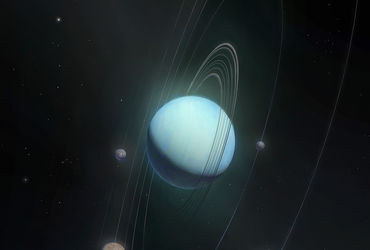

Did you know that Earth is not just a lonely planet spinning through space, but it’s actually home to tiny moons that come and go like uninvited guests at a party? Last year, astronomers were buzzing with excitement over the discovery of a mini moon that hung out with us for a few weeks, but recent studies reveal that our planet might be hosting at least six of these cosmic buddies at any given moment!

A team of researchers hailing from various countries including the US, Italy, Germany, Finland, and Sweden uncovered a fascinating truth about these mini moons. It turns out they are fragments of our very own Moon, flung into space after asteroid collisions. Imagine a cosmic game of dodgeball where our Moon loses a few bits after a rough encounter with asteroids, leaving behind smaller pieces that find themselves trapped in Earth’s gravitational embrace.

These tiny celestial objects, hovering around six feet in diameter, are classified as "lunar ejecta." They don’t just float around aimlessly; instead, they orbit our planet for several years before either escaping into the Sun’s gravitational pull or, in some unfortunate cases, crashing back to Earth or even our Moon! It's a cosmic cycle that continues as more debris is released from the Moon, giving rise to new mini moons.

Robert Jedicke, a researcher from the University of Hawaii, likened the behavior of these mini moons to a "square dance," where partners frequently change and sometimes take a break from the floor. In a study published in the journal Icarus, scientists debunked the previous belief that every new mini moon near Earth is a visitor from the asteroid belt. Instead, they concluded that approximately 18% of temporarily bound objects (TBOs) can also be classified as mini moons.

The researchers estimate that there are about 6.5 mini moons larger than 1 meter in diameter in the Earth-Moon system at any given time. To deepen their understanding, they studied two notable mini moons: Kamo'oalewa and 2024 PT5, both of which made headlines last year for orbiting our planet. These findings are not only groundbreaking but also change the way we think about our relationship with the cosmos.