The Man Who Voluntarily Got Bitten by Snakes Over 200 Times for Science!

Can you imagine willingly letting venomous snakes bite you? Sounds crazy, right? Yet, that's exactly what Tim Friede has done—over 200 times!

Tim Friede, a daring scientist from Wisconsin, recalls his most harrowing encounters with snakes in excruciating detail. His first brush with danger involved an Egyptian cobra, and less than an hour later, he faced a monocled cobra. Both of these slithery beasts are not just garden-variety snakes; they are highly venomous. And the most shocking part? These encounters were entirely intentional.

“Was it stupid? Yes,” Tim admits. But he believes his sacrifice could one day save lives. By exposing himself to these snakes, he aims to develop a method to help others survive snakebites in the future.

Over the years, Friede has recorded a staggering 202 snakebites, describing the experience with a chilling sense of normalcy: “It always burns,” he states, “and it’s always, always painful.” After those first two bites nearly 20 years ago, he was airlifted to a hospital and spent four days in a coma. But instead of backing down, Friede embarked on a journey of “self-immunization” against some of the world’s deadliest snakes.

So how does that even work? Picture a scene from The Princess Bride, where Westley builds immunity to a fictional poison by gradual exposure. That’s exactly what Friede did, by milking venom from snakes and injecting tiny doses into his body, increasing the amount over time. Jacob Glanville, the president of the biotech company Centivax, explains that this repeated exposure allowed Friede to build immunity to a wide variety of venomous snakes, including the notorious black mamba and rattlesnakes.

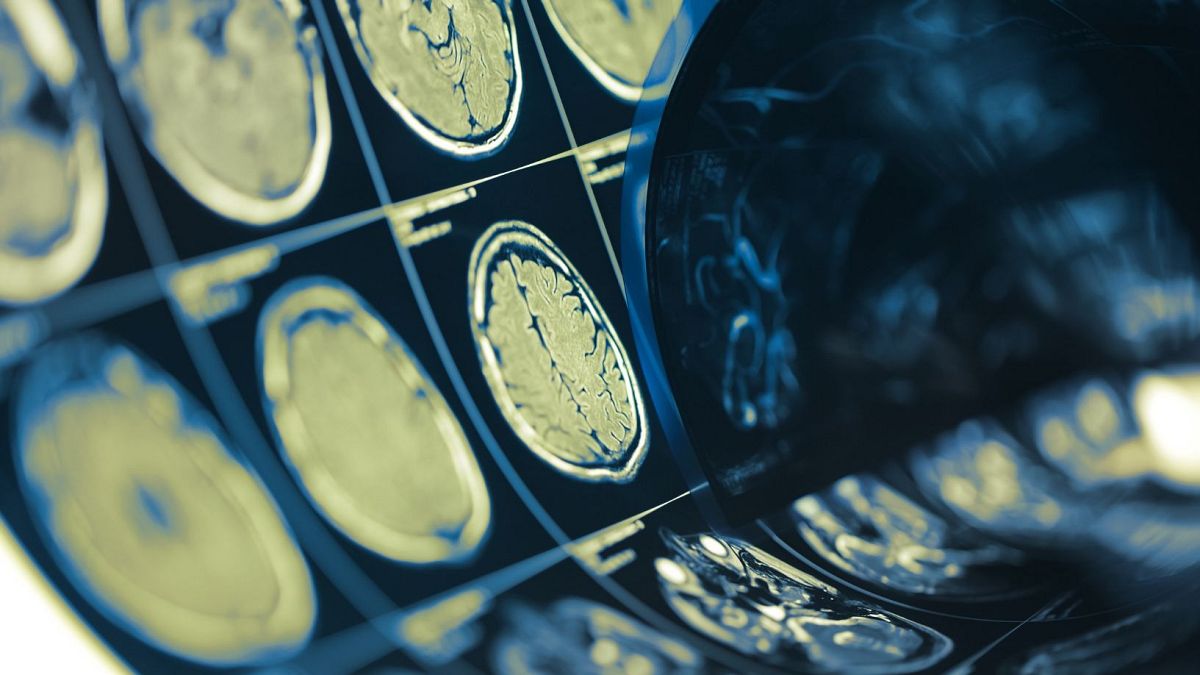

Thanks to this painstaking process, Friede was ultimately able to survive bites from snakes that would have been lethal otherwise. It’s like receiving a painful vaccine, where antibodies are created to combat toxins as well as germs. In Friede’s case, his blood is now a veritable treasure trove of unique antibodies that could potentially revolutionize treatments for snakebite victims.

Glanville’s team has harnessed these antibodies to develop a groundbreaking new antivenom. The challenge? With over 600 species of venomous snakes on the planet, creating individual antivenoms for each one is a monumental task. Inspired by Friede’s extensive experience, Glanville sought to create an antivenom capable of combating multiple snake venoms at once, ultimately leading to a phone call that Friede had been anticipating for years: “I said, ‘This might be an awkward question, but I would really like to get some of your blood.’”

The outcome of this collaboration has been promising. By using a small sample of Friede’s blood, researchers developed an antivenom cocktail that can neutralize venoms from several snake species. In tests, their concoction has shown remarkable efficacy, partially protecting mice from venomous attacks.

However, it’s important to note that this is still experimental. Andreas H. Laustsen-Kiel, a biotechnologist from Denmark, points out that while the initial results are encouraging, safety and effectiveness for human use still need thorough testing.

Currently, researchers are looking into ways to collaborate with veterinarians to treat dogs that have been bitten by snakes using their newly developed antivenom. Friede, now 57 years old, has put away the snakebites and venom injections, retiring with a staggering 654 immunizations under his belt. Regular checkups ensure that his brave ventures don’t leave a mark on his liver or kidneys.

“Tim did something remarkable, and we think it could change medicine,” Glanville praises. However, he strongly cautions against anyone trying to replicate Friede’s dangerous experiments: “We are actively discouraging anybody from trying it. No one ever needs to do it again.”