The Complex Nature of War: Realism vs. Idealism in Modern Conflicts

In contemporary discussions about warfare, one might wonder what truly hinders the successful conclusion of conflicts. Is the fear of nuclear weapons a critical factor? Perhaps it is the exorbitant costs associated with modern warfare, including medical care and the maintenance of military equipment, which render prolonged conflicts financially burdensome. Or could it be the portrayal of wars brutality by the media, which often alienates the public from engagement? Surprisingly, the answer lies deeper within the modern worldviewcharacterized by disorder and idealismthat deters societies from accepting the violent actions necessary to decisively defeat an adversary. Ultimately, this idealistic perspective prevents wars from being won, rooted in an unwillingness to acknowledge that evil exists and that sometimes, it requires dirty hands to confront it.

One prominent figure, Higgins, articulates this viewpoint succinctly: Its simple economics. Today its oil, right? In ten or fifteen years, food, plutonium, and maybe even sooner. His conversation partner, Turner, queries whether they should consult peoples opinions on such matters. Higgins promptly responds, cautioning that the true test will arise during times of scarcity. Ask them when theyre running out. Ask them when theres no heat in their homes and theyre cold. Ask them when their engines stop. Ask them when people whove never known hunger start going hungry. You want to know something? They wont want us to ask them. Theyll just want us to get it for them.

This dialogue encapsulates a long-standing narrative of realism versus idealism. Americans, due to their geographic advantages and other privileges, often find themselves detached from the agonies and hardships wrought by war. Individuals like Turner are emblematic of a society that can afford to perceive evil as something that humanity vanquished long ago. In stark contrast, Higgins embodies a more pragmatic understanding, shaped by decades of confrontation with global evils. He recognizes that state security demands a willingness to engage in morally ambiguous actions to safeguard citizens in a flawed world.

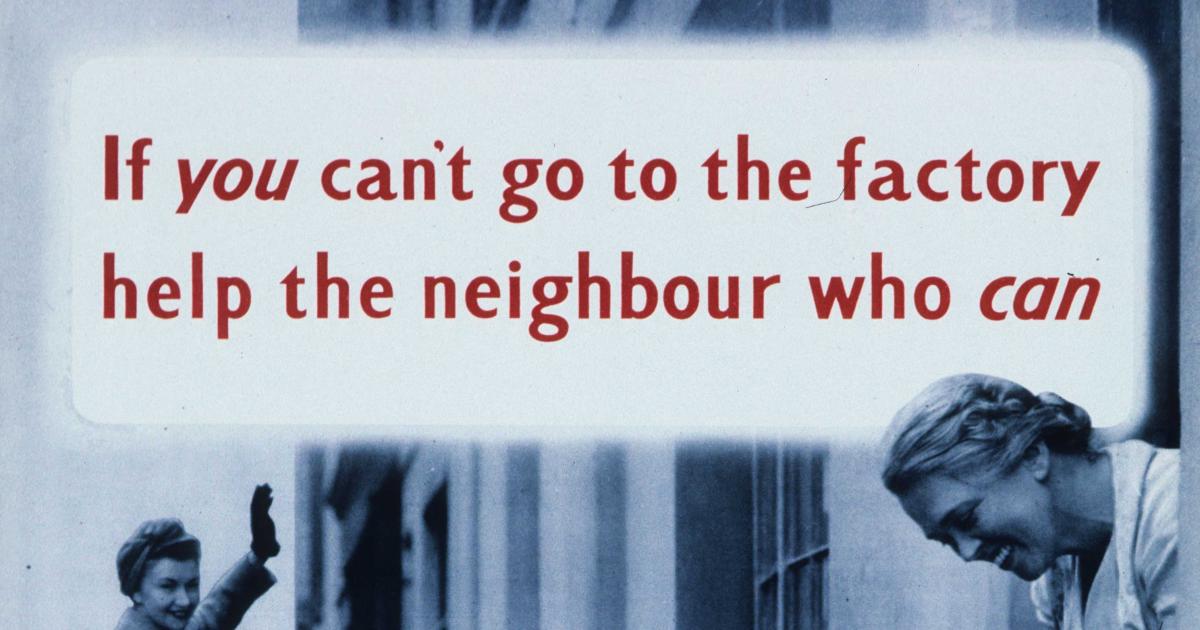

While the costs associated with warfare are indeed a pressing concern, the future remains unpredictable, and circumstances may arise that compel societies to confront those costs. The ancient historian Thucydides offers wisdom on the subject, noting, In peace and prosperity states and individuals have better sentiments, because they do not find themselves suddenly confronted with imperious necessities; but war takes away the easy supply of daily wants and so proves a rough master that brings most mens characters to a level with their fortunes. This perspective starkly contrasts the West's tendency to view history through a lens of judgment, often forgetting the sobering realities faced by those on the frontline in conflict zones such as Ukraine, the Middle East, and the Sahel region of Africa. War, unfortunately, remains an integral chapter in the saga of Western civilization.

Historically, the ancient Mediterranean serves as a vivid example of this eternal struggle. It is overly simplistic and misleading to view antiquity as merely an era of conquest and ignorance. Individuals in that age encountered death and suffering from the moment of birth in ways that modern society cannot begin to comprehend. With infant mortality rates around 30 percent and rampant diseases claiming lives without clear scientific understanding, the specter of death was a constant companion. War was one of many forms of demise, yet scholars like Robert Garland observe that The corpse itself inspired little horror. The ancient Greeks had a profound understanding of life as a cycle of struggle and conflict. Around 700 BC, the poet Hesiod reflected on this concept of stasisa state of unrest that inexorably leads to war and suffering, stating that stasis encourages war and evil battle, wretched; no man loves her, but by necessity, through the will of the deathless ones, they honor the oppressive Strife.

The ancient worldview offers a more realistic perspective on the necessity of defense mechanisms employed by states to protect their citizens from violence. Civilizations such as the Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, and Romans were embroiled in continuous warfare, both internally and externally, as they fought for survival. They recognized that nonstate actors on their fringes also engaged in endemic warfare, illustrating that conflict transcends theological, cultural, or political boundaries. As we continue to overlook the wisdom of history, we risk succumbing to contemporary narratives that obscure the darker truths of human nature. Accepting these realities is imperative.

St. Augustine provides insights into another crucial aspect that hampers the possibility of lasting peace: mankinds libido dominandi, or the lust for domination. Throughout his life, Augustine wrestled with the dilemma of how a moral individual engages with an immoral world. This internal struggle reached a pivotal moment during the sack of Rome in AD 410, which led him to fully comprehend the weight of humanitys fallen nature. In his seminal work, City of God, Augustine articulates, Even peace is a doubtful good, since we do not know the hearts of those with whom we wish to maintain peace, and even if we could know them today, we should not know what they might be like tomorrow. He recognizes that while humanity can strive to combat this lust for power, it is an inherent aspect of our existence that will persist in our flawed world.

The struggle between the perspectives of Higgins and Turner encapsulates the broader debate on the realities of warfare. Historians like Herodotus also acknowledge this tension; he concludes The Histories with praise for King Cyrus the Great of Persia, who cautions against the complacency bred by comfortable circumstances: Soft countriesbreed soft men. It is not the property of any one soil to produce fine fruits and good soldiers too. In a world increasingly dominated by advanced military technologiesranging from hypersonic weaponry to innovative quantum processorsthe true determinant of national security remains the will to defend against those who seek to dominate.