Federal Minimum Wage: A Stark Reality of Economic Insecurity

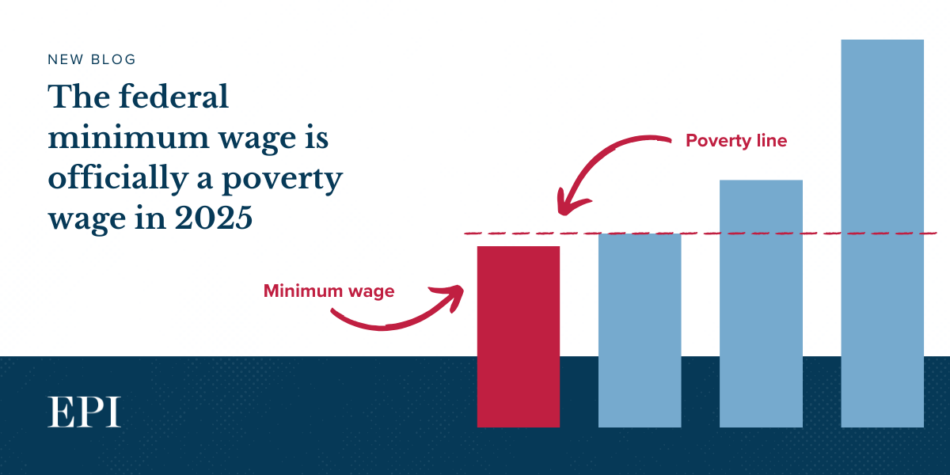

As we look ahead to 2025, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour is projected to become a stark indicator of economic vulnerability, officially qualifying as a poverty wage. A single adult working full-time at this rate will earn only $15,080 annually, a figure that falls significantly below the federal poverty threshold of $15,650, as set by the Department of Health and Human Services. This alarming situation underscores a critical flaw in how the federal government measures poverty, revealing just how far the minimum wage lags behind what is necessary for economic security for millions of American workers and their families.

The minimum wage, when set appropriately, serves as a powerful tool to bolster the economic well-being of low-wage workers while simultaneously helping to alleviate poverty levels. However, instead of addressing this glaring inadequacy in our economic safety net, many congressional Republicans are advocating for policies that impose stringent work requirements on safety net programs and aim to reduce funding for Medicaid. Proponents of these measures frame them as efforts to encourage work and maintain the dignity associated with employment. Yet, these policies overlook the harsh realities of low-wage work and risk exacerbating hardships for vulnerable workers, ultimately yielding no economic benefits for these individuals or the broader economy.

The origins of the minimum wage can be traced back to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which aimed to protect American workers from the perils of insufficient wages that could not cover the essentials of daily living. Unfortunately, the current federal minimum wage is falling short of this mission, largely due to an unprecedented period of legislative inaction. Since Congress last increased the federal minimum wage in July 2009, inflation has eroded its value by approximately 30%. This decline has placed the annual earnings of full-time minimum wage workers far below the established poverty line for households of all sizes.

Figure A illustrates this disheartening comparison, showing the substantial gap between the federal minimum wage and the poverty guidelines for various household sizes. For instance, the poverty line for a single-person household stands at $15,650, while a full-time worker earning the minimum wage brings in only $15,080. For a two-person household, the threshold rises to $21,150, and for a four-person household, it leaps to $32,150.

This stark contrast highlights the inadequacies of the current economic framework, severely underestimating the plight of these workers and their families. The federal poverty guidelines, which determine eligibility for public assistance programs like Medicaid and SNAP, stem from the Census Bureaus official poverty measure (OPM). Unfortunately, this measure only considers a minimal food budget based on costs from 1963. A more comprehensive approach exists in the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which considers a wider range of living expenses, including housing, utilities, and healthcare. According to the SPM, more than 10 million workers (approximately 7%) aged 18 to 64 lived in poverty as of 2023, compared to just 4.5% reflected in the OPM.

In response to the inadequate federal minimum wage, 30 states and Washington, D.C., have taken the initiative to increase their minimum wage beyond the federal standard. In stark contrast, 20 states continue to adhere to the federal minimum, leaving approximately 11.8 million workers earning less than $17 per hour. This means that over 1 in 5 workers in these states are living on wages that are insufficient for basic survival, particularly in the South, where low wages are more prevalent. The stagnation of the federal minimum wage has permitted Southern policymakers to uphold low wage levels, further entrenching poverty in the region.

Research consistently demonstrates that increasing the minimum wage can boost the earnings of low-wage workers without significantly impacting employment levels. An analysis of legislation proposed in 2021 to incrementally raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour indicated that this move could lift between 1.8 to 3.7 million individuals out of poverty, including up to 1.3 million children. Despite resistance from the business sector and conservative lawmakers, public support for raising the minimum wage remains robust. Recently, Congress members, led by Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Bobby Scott, reintroduced the Raise the Wage Act, which aims to gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $17 an hour, benefiting over 22.2 million workers, including 4.2 million living in households below the poverty line.

On the other hand, the Republican agenda appears to threaten the very foundation of economic security for low-income workers. Their proposed budget cuts for 2025 target essential social safety net programs, particularly Medicaid, while also tightening work requirements for programs like SNAP. These reforms are projected to hurt low-income families who depend on these programs to improve their living standards. In fact, in 2023 alone, safety net programs managed to lift over 7 million individuals above the poverty line.

Republicans have argued that cutting benefits and imposing strict work requirements will motivate people to seek employment. This rationale overlooks a crucial fact: two-thirds of non-elderly Medicaid enrollees and over 85% of working-age adults receiving SNAP are already employed. This narrative is steeped in historical biases and stereotypes suggesting that welfare recipients are primarily lazy or unmotivated. Analyzing the economic repercussions of these proposals, its evident that these policies would lead to increased hardships for low-income Americans without yielding tangible economic benefits. For instance, the proposed Medicaid cuts would substantially reduce incomes for low-income families, with families in the bottom 20% facing an income drop of approximately 7.4%. Moreover, Medicaid is a critical investment in the health and future of low-income children, contributing to improved educational and financial outcomes over their lifetimes.

Adding work requirements to benefit programs has also proven ineffective. Studies show no significant improvement in employment outcomes in places where such policies have been implemented. Instead, these requirements simply create barriers for individuals trying to access the benefits they qualify for.

The unpredictable nature of low-wage jobs, characterized by last-minute scheduling changes and frequent turnover, makes it exceptionally challenging for workers to meet consistent work-hour requirements. As a result, enforcing work requirements effectively acts as a reduction in benefits for existing participants and limits new applicants who have little control over their work conditions.

In conclusion, the federal minimum wage is a crucial mechanism for enhancing the economic safety of low-wage workers. However, Republican lawmakers have persistently opposed any increases to this wage while pursuing policies that threaten to cut Medicaid and restrict access to essential safety net programs. If enacted, the combination of tax cuts for the wealthy and reductions in Medicaid would disproportionately impact workers in the bottom 40% of the income distribution while enriching the top 1%. These cuts would also have a particularly detrimental effect on communities of color, who are more likely to rely on Medicaid.

To genuinely lift families out of poverty and enable their full participation in the workforce, lawmakers should prioritize policies that raise wages and improve access to quality jobs. By perpetuating low wages and complicating benefit access, lawmakers are undermining the very resources that low-income households need to thrive.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which used to be known as the food stamp program, plays a vital role in providing essential nutrition assistance to low-income families in the United States. It is particularly important to note that SNAP imposes work requirements for most beneficiaries aged 16 to 59 who are capable of working, and even more stringent requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs).